|

On eBay Now...

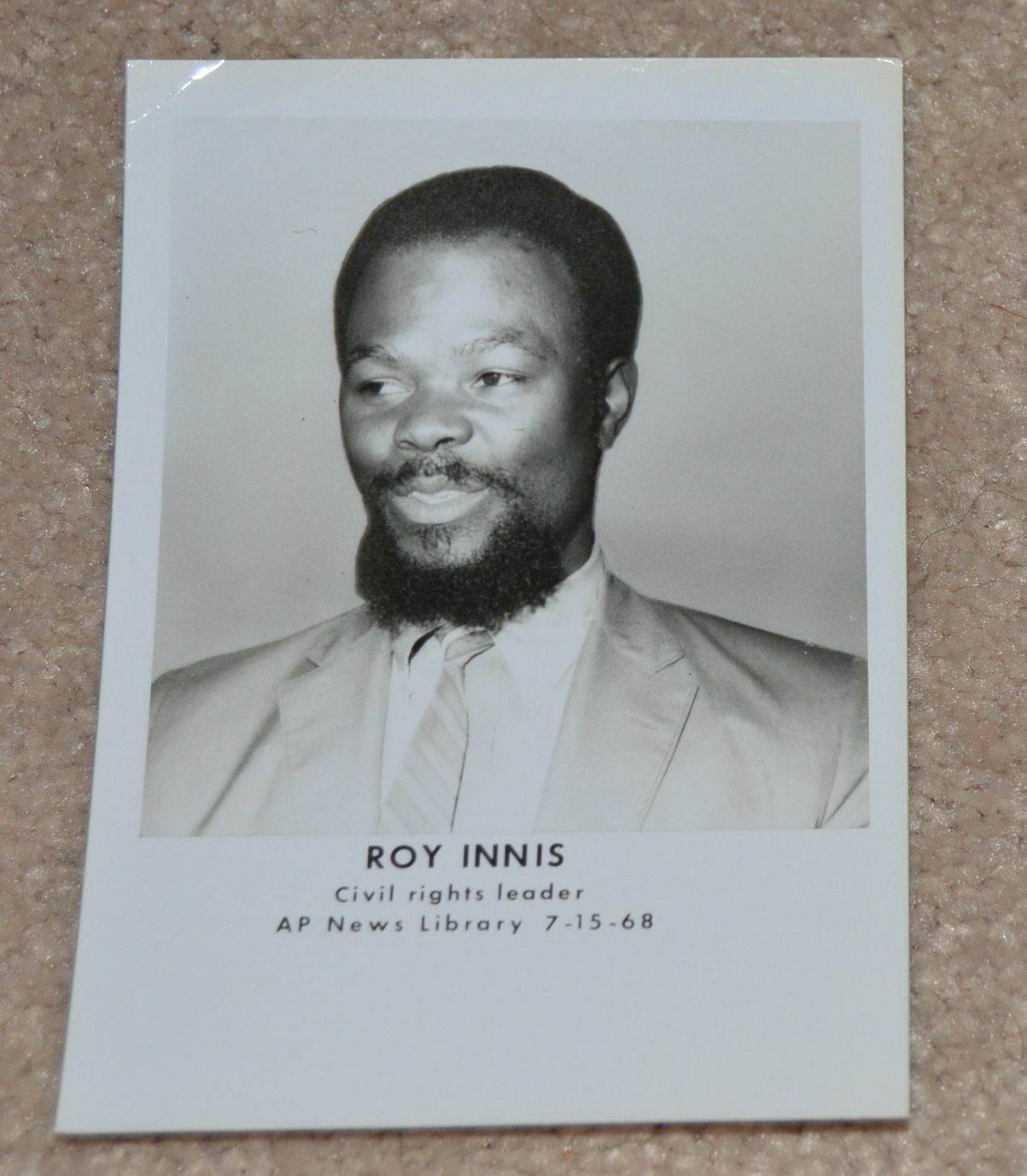

1968 ROY INNIS VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER AFRICAN AMERICAN For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1968 ROY INNIS VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER AFRICAN AMERICAN:

$279.77

ROY INNIS VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO FROM 1968 MEASURING 3.5X5 INCHES OF THIS AFRICAN AMERICAN CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER

Roy Emile Alfredo Innis (June 6, 1934 – January 8, 2017) was an American activist and politician. He had been National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) since his election to the position in 1968.

One of his sons, Niger Roy Innis, serves as National Spokesman of the Congress of Racial Equality.Contents1 Early life2 Early civil rights years3 Leadership of CORE4 Politics5 Criminal justice and National Rifle Association6 Controversy7 Political campaigns8 Death9 Bibliography10 References11 External linksEarly lifeInnis was born in Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands in 1934.[1] In 1947, Innis moved with his mother from the U.S. Virgin Islands to New York City, where he graduated from Stuyvesant High School in 1952.[2] At age 16, Innis joined the U.S. Army, and at age 18 he received an honorable discharge. He entered a four-year program in chemistry at the City College of New York. He subsequently held positions as a research chemist at Vick Chemical Company and Montefiore Hospital.[3]

Early civil rights yearsInnis joined CORE's Harlem chapter in 1963. In 1964 he was elected Chairman of the chapter's education committee and advocated community-controlled education and black empowerment. In 1965, he was elected Chairman of Harlem CORE, after which he campaigned for the establishment of an independent Board of Education for Harlem.

In early 1967, Innis was appointed the first resident fellow at the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC), headed by Dr. Kenneth Clark. In the summer of 1967, he was elected Second National Vice-Chairman of CORE.

Leadership of COREInnis was selected National Chairman of CORE in 1968 a contentious convention meeting.[4][5] Innis initially headed the organization in a strong campaign of Black Nationalism. White CORE activists, according to James Peck, were removed from CORE in 1965, as part of a purge of whites from the movement then under the control of Innis.[6] Under Innis' leadership, CORE supported the presidential candidacy of Richard Nixon in 1972. This was the beginning of a sharp rightward turn in the organization.[7]

Politics

Roy Innis (2nd from left) and then wife Doris Funnye Innis (center) with a delegation from CORE is greeted by Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta (left).Innis co-drafted the Community Self-Determination Act of 1968 and garnered bipartisan sponsorship of this bill by one-third of the U.S. Senate and over 50 congressmen. This was the first time in U.S. history that CORE or any civil rights organization drafted a bill and introduced it into the United States Congress.[8]

In the debate over school integration, Innis offered an alternative plan consisting of community control of educational institutions. As part of this effort, in October 1970, CORE filed an amicus curiae brief with the U.S. Supreme Court in connection with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971).

Innis and a CORE delegation toured seven African countries in 1971. He met with several heads of state, including Kenya's Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania's Julius Nyerere, Liberia's William Tolbert and Uganda's Idi Amin, who was awarded a life membership of CORE.[9] Innis met with Amin and the aforementioned African statesmen as part of his CORE campaign drive for finding jobs in Africa for black Americans. In 1973 he became the first American to attend the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in an official capacity. In 1973, Innis was scheduled to participate in a televised debate with Nobel-winning physicist William Shockley on the topic of black intelligence. According to sources, Innis pulled out of the debate at the last moment because the student society at Princeton University organizing the event refused to allow the press and the public into the event. The debate went forward with Dr. Ashley Montagu replacing Innis.[10]

Criminal justice and National Rifle AssociationInnis was long active in criminal justice matters, including the debate over gun control and the Second Amendment. After losing two sons to criminals with guns, he became an advocate for the rights of law-aoffering citizens to self-defense.[11] A Life Member of the National Rifle Association,[11] he also served on its governing board.[12][13] Innis also chaired the NRA's Urban Affairs Committee and was a member of the NRA Ethics Committee, and continued to speak publicly in the US and around the world in favor of individual civilian ownership of firearms, gun issues, and individual rights[11]

Innis lost two of his sons to criminal gun violence. His eldest son, Roy Innis, Jr., was killed at the age of 13 in 1968. His next oldest son Alexander, 26, was shot and slain in 1982.[14] Innis told Newsday in 1993 "My sons were not killed by the KKK or David Duke. They were murdered by young, black thugs. I use the murder of my sons by black hoodlums to shift the problems from excuses like the KKK to the dope pushers on the streets."[15]

ControversyInnis was noted for two on-air fights in the middle of TV talk shows in 1988. The first in the midst of an argument about the Tawana Brawley case during a taping of The Morton Downey, Jr. Show, Innis shoved Al Sharpton to the floor.[16] Also that year, Innis was in a scuffle on Geraldo with white supremacist John Metzger.[17] The skirmish started after Metzger, son of White Aryan Resistance founder Tom Metzger, called Innis an "Uncle Tom", and Innis grabbed the seated Metzger's throat, appearing to choke him.[18][19]

Innis raised American volunteers to fight for UNITA, an Angolan rebel army fighting the communist government.[20] UNITA was also supported by Uganda[citation needed] and apartheid-era South Africa.

Prosperity USA, a non-profit run by aides of presidential candidate Herman Cain, attracted controversy after it gave a $100,000 donation to CORE shortly before Cain's speech at a CORE event.[21]

Political campaignsIn 1986, Innis challenged incumbent Major Owens in the Democratic primary for the 12th Congressional District, representing Brooklyn. He was defeated by a three-to-one margin.

In the 1993, New York City Democratic Party mayoral primary, Innis challenged incumbent David Dinkins, the first African-American to hold the office. Given his conservative positions on the issues, he explained that "the Democratic Party is the only game in town. It's unfortunate that we have a corrupt one-party, one ideology system in New York City, and I'd like to change that. But being a Democrat doesn't mean you have to be a fool." During his own campaign, Innis also appeared at fundraising events for the Republican candidate Rudolph Giuliani. Innis received 25% of the vote in the four-way race with a majority of his votes coming from multi-ethnic areas, while he failed in less culturally diverse Assembly Districts. Innis lost to Dinkins, who then lost to Giuliani in the general election.

In February 1994, his son, Niger, who ran his primary campaign, suggested that Innis would also challenge incumbent governor Mario Cuomo in the Democratic primary.

In 1998, Innis joined the Libertarian Party and gave serious consideration to running for Governor of New York as the party's candidate that year. He ultimately decided against running, citing time restrictions related to his duties with CORE.[22]

Innis served as New York State Chair in Alan Keyes' 2000 presidential campaign.[23]

DeathInnis died on January 8, 2017, at the age of 82, from Parkinson's disease.[1]

Roy Innis, the autocratic national leader of the Congress of Racial Equality since 1968, whose right-wing views on affirmative action, law enforcement, desegregation and other issues put him at odds with many black Americans and other civil rights leaders, died on Sunday in Manhattan. He was 82.

The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease, a statement from CORE said.

In a stormy career marked by radical rhetoric, shifting ideologies, legal and financial troubles and quixotic runs for office, Mr. Innis led CORE through changes that mirrored his own evolution from black-power militancy in the 1960s to staunch conservatism resembling a modern Republican political platform.

He came to prominence after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young and James Farmer had taken command of the civil rights movement and did not share their commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience. Nor did he embrace CORE’s pioneering roles in desegregation — school boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides through the South and voter registration drives that led to the murders of the activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964.

Though court decisions and new laws banned discrimination in education, employment and public accommodations, Mr. Innis was disillusioned by that progress, saying integration robbed black people of their heritage and dignity. He pronounced it “dead as a doornail,” proclaimed CORE “once and for all a black nationalist organization” and declared “all-out war” on desegregation.

Under his black-power banner, which Mr. Innis called “pragmatic nationalism,” he purged whites from CORE’s staff and allowed the organization’s white membership to wither. He espoused segregated schools to encourage black achievement, black self-help groups, black business enterprises and community control of the police, fire, hospital, sanitation and other services in poor black neighborhoods.

This is your last free article.Subscribe to The TimesBlack nationalism was hardly a new idea. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had already moved from integrationist to separatist aims. Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam and the poet Amiri Baraka followed in the footsteps of Marcus Garvey, who after World War I had attracted millions of American blacks to a “back to Africa” movement.

But most black Americans regarded black power as too radical, and the creation of separate black institutions in America too remote.

Editors’ Picks

She’s Taking on Elon Musk on Solar. And Winning.

10 Years Later, an Oscar Experiment That Actually Worked

Why Do Trump Supporters Support Trump?

ImageIn 1968, Mr. Innis, second from right, was chosen as national director of the Congress of Racial Equality.In 1968, Mr. Innis, second from right, was chosen as national director of the Congress of Racial Equality.Credit...BettmannIn the early 1970s, Mr. Innis toured Africa, visiting Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania and Idi Amin in Uganda. He made Amin a life member of CORE and predicted that he would lead a “liberation army to free those parts of Africa still under the rule of white imperialists.” He later urged black Vietnam veterans to assist anti-Communist forces fighting in Angola.

As his black nationalism converged with his increasingly conservative politics, Mr. Innis supported Richard M. Nixon for president in 1968 and 1972, and Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s. Blacks voted overwhelmingly against both men, but Mr. Innis sided with them in clashes with civil rights leaders who criticized their records. Mr. Innis urged both presidents to reach out to blacks directly and urged blacks to join the Republican Party.

In 1981, after New York State accused him of illegal fund-raising and of misusing $500,000 of CORE’s money, Mr. Innis admitted no wrongdoing but agreed to repay $35,000 and accept tighter financial controls. In 1986, the Internal Revenue Service accused him of failing to report $116,000 in income. He did not contest the accusations and was assessed $56,000 in back taxes and $28,000 in civil penalties.

Mr. Innis survived lawsuits and efforts by CORE members to depose him. But as its membership declined, CORE increasingly aligned itself with corporations, including Monsanto and Exxon Mobil. Their donations became a primary source of funds, while CORE lent its support to their causes.

Mr. Innis acknowledged that his loss of two sons to gun violence in New York — Roy Jr., 13, in 1968, and Alexander, 26, in 1982 — influenced his decision to oppose gun control and defend citizens’ rights to carry arms in self-defense. He became a life member and a director of the National Rifle Association.

In 1984, Mr. Innis ardently supported Bernard H. Goetz, the white gunman who shot four black youths in a subway confrontation that he called an attempted mugging and that they called panhandling. The episode, with Mr. Goetz cast as a vigilante, came to symbolize New Yorkers’ frustration with soaring crime rates. A jury found him guilty only of carrying an unlicensed firearm.

Two years later, with Mr. Goetz at his side, Mr. Innis challenged Representative Major R. Owens, a black Brooklyn congressman, in the Democratic primary. Mr. Innis called affirmative action programs “morally corrupt” and promised to sit with the Republicans if he won. He lost by a three-to-one ratio.

Mr. Innis supported Robert H. Bork’s Supreme Court nomination by President Reagan in the late ’80s and Clarence Thomas’s nomination by President George Bush in the early ’90s. Both were Federal Appeals Court jurists for the District of Columbia who said they favored interpreting the Constitution in light of its framers’ intentions. The Senate rejected Judge Bork but approved Judge Thomas.ImageMr. Innis tended to make his alliances with the political right. In 2005, he threw his support behind Samuel A. Alito Jr., who had been nominated to the Supreme Court by President George W. Bush.

Credit...Lauren Victoria Burke/Associated PressA favorite of conservative talk shows, Mr. Innis twice engaged in televised scuffles in 1988. On “The Morton Downey Jr. Show,” he erupted at challenges to his leadership and shoved the Rev. Al Sharpton to the floor. On “Geraldo,” he choked John Metzger of the White Aryan Resistance, who had called him an “Uncle Tom,” and the host, Geraldo Rivera, suffered a broken nose in the ensuing brawl.

In 1993, Mr. Innis challenged David N. Dinkins, New York’s first black mayor, in the Democratic mayoral primary. Mr. Innis pledged to fight homelessness by separating “the indolent from the indigent,” and to “give a voice to the silent majority in both the white and black communities.” Mr. Dinkins trounced him and narrowly lost the general election to Rudolph W. Giuliani, who ran on both the Republican and Liberal lines, and whom Mr. Innis supported.

In recent years, CORE’s membership declined, and while the organization continued to fight discrimination in jobs and housing and to provide training for single parents on welfare, critics said it no longer played a major role in civil rights and had become an ally of corporations and interests alien to its original charter.

Roy Emile Alfredo Innis was born on June 6, 1934, in St. Croix, the United States Virgin Islands, to Alexander and Georgianna Thomas Innis. His father, a police officer, died when Roy was 6. He moved to New York with his mother in 1946.

He attended Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan but dropped out at 16 to join the Army. When it was discovered that he was underage, he was sent home. He graduated from Stuyvesant in 1952, studied chemistry at City College of New York until 1958, then worked as a research chemist for Vicks Chemical Company and Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx.

Mr. Innis rarely spoke of his family, about which little is known. He lived in Harlem and was married several times, and the statement from CORE listed 10 children — Cedric, Winston, Kwame, Niger, Kimathi, Mugabe, Arenza, Lydia, Patricia and Corinne — and “a host of grandchildren.”

Mr. Innes joined the Harlem chapter of CORE in 1963. His second wife, Doris Funnye, was also active in civil rights. At the time, CORE was the most radical and action-oriented of the established civil rights organizations. He was named chapter chairman in 1965 and three years later, outmaneuvering rivals, succeeded Floyd McKissick as CORE’s national director. He held that title until becoming national chairman in 1982.

“In America today,” Mr. Innis told a national CORE convention, “there are two kinds of black people: the field-hand blacks and the house niggers. We of CORE — the nationalists — are the field-hand blacks. The integrationists of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People are house niggers.”

The reaction was explosive, and it set the tone for decades of strife.