|

On eBay Now...

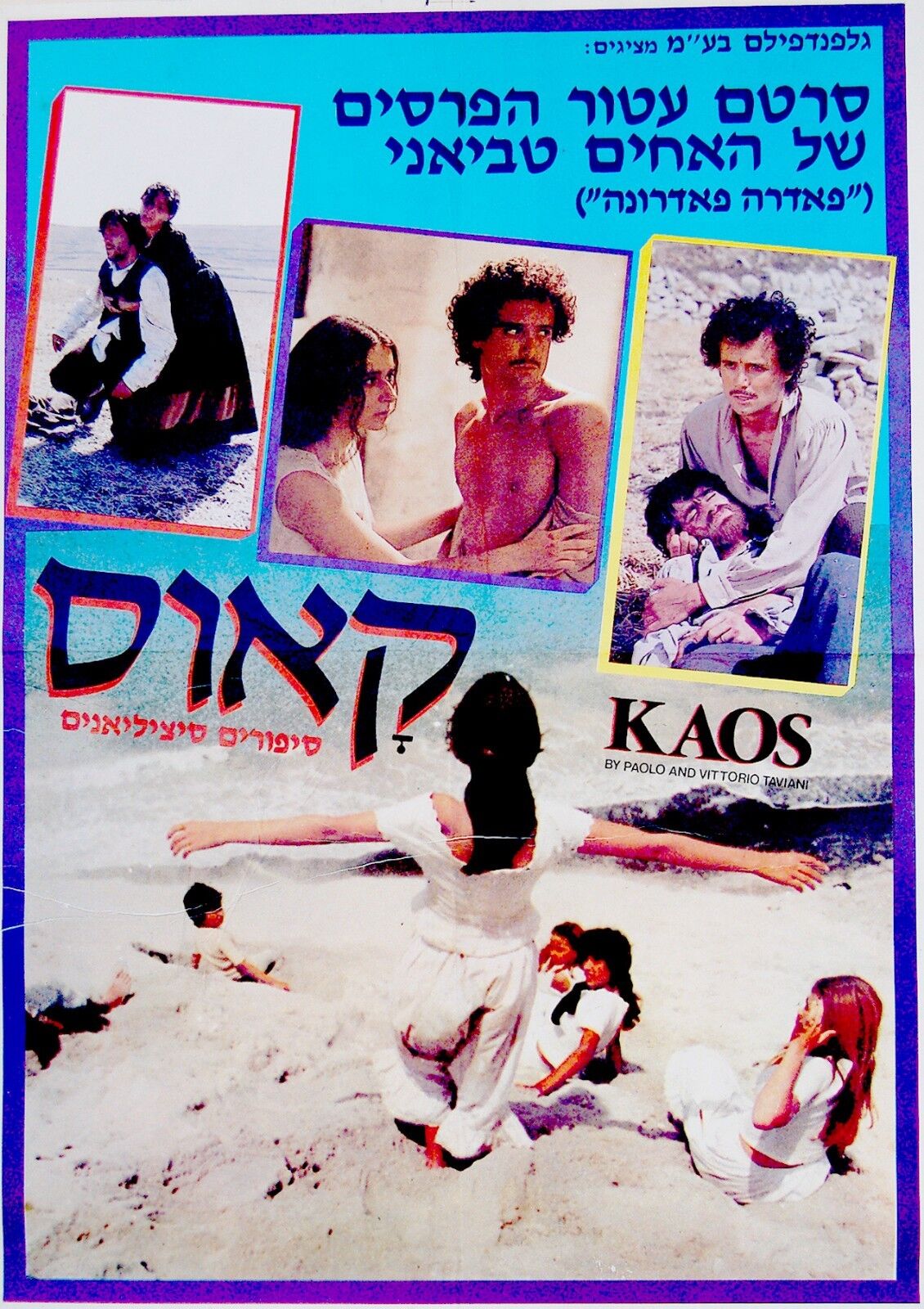

1984 Israel RARE MOVIE POSTER Film KAOS Hebrew TAVIANI BROTHERS Pirandello CHAOS For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1984 Israel RARE MOVIE POSTER Film KAOS Hebrew TAVIANI BROTHERS Pirandello CHAOS:

$95.00

DESCRIPTION : Here for sale is an EXCEPTIONALY RARE and ORIGINALillustrated POSTER for the ISRAEL premiere release ofthe BROTHERS TAVIANI legendary awards winning film\" KAOS \" ( Also CHAOS - Based on PIRANDELLO stories ) inISRAEL. This is an original Israeli Hebrew design , Specificaly made for the Israeli Theatre halls. Text in HEBREW and ENGLISH/ITALIAN .Size around 27\" x19\" . Printed in vivid colors . The condition is quite good. Somewhat creased , Nothing that a framed glass wouldn\'t hide. ( Pls look at scanfor accurate AS IS images )Poster will be sent rolled in a specialprotective rigid sealed tube.

AUTHENTICITY :The POSTER is fullyguaranteed ORIGINALfrom 1984 , It is NOT a reproduction or a recentlymadereprint or an immitation ,Itholds awith life longGUARANTEE for itsAUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY. PAYMENTS: Payment method accepted : Paypal & All credit cards.

SHIPPMENT: SHIPP worldwide via registered airmailis $ 29.Posterwill be sent rolled in a special protective rigid sealed tube. Will besentaround 5-10 days after payment .

Kaos (also Chaos in the American release) is a 1984 Italian drama film directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani based on short stories by Luigi Pirandello (1867–1933). The film\'s title is after Pirandello\'s explanation of the local name Càvusu of the woods near his birthplace in the neighborhood of Girgenti (Agrigento), on the southern coast of Sicily, as deriving from the ancient Greek word kaos. Contents 1 Plot2 Cast3 Awards and reception4 Reviews5 External links Plot The film depicts four short stories from Pirandello\'s 15-volume series Novelle per un anno, which play around his birthplace in the 19th century. A raven, which in the introduction is shown to get a bell around his neck from locals, leads one from one story to the next. L’altro figlio (\"The Other Son\") is about a mother whose two sons have emigrated to the United States. She hasn\'t heard from them since (14 years ago), but she still favors them over a third son who has stayed behind and tries to help and please his mother. The reason for her completely shunning him are explained in flashbacks to events in 1848.Mal di luna (\"Moonsickness\") Three weeks after their honeymoon, Sidora discovers that, during the full moon, her husband Batà spends the night howling outside like a werewolf and scratching to get back in. Batà tries to save his marriage by allowing her to have the handsome Saro spend the full-moon nights at their place to protect Sidora.La giara (\"The Jar\") In this comedic section, a feudal landlord (Don Lollò) orders a very large jar for his olive oil, but the new jar breaks almost immediately under mysterious circumstances. The great \"jar-fixer\" Zi\' Dima, famous for his secret-recipe glue, is called to repair the jar, but Zi\' Dima manages to fix the jar with himself in it and Don Lollò refuses to break the jar again to let him out.Requiem Motivated by the imminent death of their founding father, farmers in a remote hamlet on grounds owned by a baron try to obtain the rights to bury their dead locally rather than in the town, which is over a day\'s hike away. The baron refuses and carabinieri escort the peasants back to their hamlet to break down the beginnings of a graveyard the peasants are building. An epilogue, Colloquio con la madre (\"Conversing with Mother\"), of similar length as the stories, describes Pirandello\'s fictional visit home many years after his mother has died. He asks his mother to retell the story of a trip to Malta she took as a child to visit her exiled father. The ending sequence showed children sliding down the vast slopes of white pumice that flowed into the sea on the island of Lipari. Cast Margarita Lozano as Mariagrazia (in \"L\'altro figlio\'\")Claudio Bigagli as Batà (in \"Mal di luna\")Enrica Maria Modugno as Sidora (in \"Mal di luna\")Franco Franchi as Zi\' Dima (in \"La giara\")Ciccio Ingrassia as Don Lollò (in \"La giara\")Biagio Barone as Salvatore (in \"Requiem\")Omero Antonutti as Luigi Pirandello (in \"Colloquio con la madre\")Regina Bianchi as Pirandello\'s mother (in \"Colloquio con la madre\")Massimo Bonetti as Saro (in \"Mal di luna\" and \"Colloquio con la madre\") Awards and reception Kaos won the 1985 David di Donatello awards for best production and best screenplay and was nominated for best music. It also won the Silver Ribbon award for best screenplay. The film was very well received by critics, but its length may have prevented wide exposure. In his 2007 book The Best Movies of Our Years, M. Owen Lee considered it the best movie to come out locally in 1986 [sic]. Chaos (1984) PIRANDELLO TALES IN THE TRAVIANNI BROTHERS\' \'KAOS\' By JANET MASLIN Published: October 13, 1985 \'\'K AOS,\'\' the Greek word for \'\'Chaos,\'\' is a curious title for the new film by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, a film with a profound and stirring sense of natural order. Adapted loosely from stories by Luigi Pirandello (the title in fact comes from a Pirandello quotation about the derivation of \'\'Cavusu,\'\' the name of a forest near his native village), \'\'Kaos\'\' tells four separate tales of Sicilian life. These fables, plus an epilogue about the author himself, are united by their shared imagery, their strong sense of community, their final ironies and the clear, graceful way in which they are told. \'\'Kaos\'\' unfolds with the rapturous simplicity that was most apparent in \'\'Padre, Padrone,\'\' the first of the Taviani brothers\' films to be released here, and that is even more mesmerizing this time. Yet \'\'Kaos\'\' also has an edge. The Pirandello influence makes itself felt in the twists of fate that turn each tale\'s principals against prevailing values, and in the bittersweet note on which the stories conclude; as for the Tavianis, their contribution is an earthy, knowing storytelling style that finds a folk wisdom in the characters\' humanity. In any case, the task of adapting Pirandello proves particularly felicitous for these screenwriter-directors. Rigorous and eloquent, effortlessly poetic, \'\'Kaos\'\' is the Tavianis at their best. The film opens with spectacular Sicilian scenery and a sequence in which a group of shepherds find a male crow on a nest full of eggs. Some suggest killing the bird for this transgression, or at the very least humiliating him; instead, one shepherd ties a bell around the bird\'s neck and sets him free. This bird then circles his way through the subsequent stories, making his own music and serving as a stubborn, indefatigable reminder of nature\'s mysteries. Here and elsewhere, the film finds an inexplicable rightness in phenomena that seem to defy reason. The first story, \'\'The Other Son,\'\' concerns a Sicilian mother (Margarita Lozano) pining for two boys who have emigrated to Santa Fe. They left 14 years earlier and have not communicated with her since. But she continues to send them loving letters, dictating her messages to a bored young girl who takes down only scribbles, ignoring the mother\'s words completely. The mother\'s longing for her sons also induces her to follow each group of prospective emigrants marching away from her village, in hopes of finding someone who will carry word to Santa Fe. During one of these marches, the emigrants stop for a break of several hours - and it is the Tavianis\' unique, if romantic, feeling for communal scenes that enables them to let these peasants re-create their village life in an open field, without even requiring many props. Then, across the field, we see a man watching over a few cattle, even though the land is too barren for them to graze. Neither he nor the cattle belong there, but he is following his mother - the same mother who pines so incessantly for her other offspring. The rest of the tale provides the mother\'s account of how this strange situation can have come to be. \'\'Moon Sickness\'\' concerns a lonely young bride, Sidora (Enrica Maria Modugno), who has been living only briefly with her new husband Bata (Claudio Bigagli) when the first full moon of their marriage occurs. Bata warns her to bar the doors and windows, then goes outside and howls so horribly that he leaves his wife petrified. In the morning, Bata is shamed by his behavior and goes to the village square, where - in a sequence especially well suited to the Tavianis\' affectionate folk humor - he makes an anguished confession to the closed doors and shuttered windows that surround him. Nobody peers out at Bata, but somebody, somehow, provides him with a chair. There is never any doubt that the rest of the villagers are just behind their shutters, listening to every word. In another lovely sequence, Bata explains that his troubles began when his mother, working late in the fields when he was an infant, exposed the baby to his first full moon. Since then, the moon has driven him to temporary madness, and now he fears for his wife\'s safety. When a solution is suggested - that Sidora be watched over by Saro (Massimo Bonetti), a handsome cousin whom she almost married anyhow - the situation becomes much more complicated. And it grows even more so when, on the night of the next full moon, Sidora hides in her cottage and makes plans for herself and Saro, without knowing that outside it has grown very cloudy. Of the four stories, it is \'\'Moon Sickness\'\' that has the most sadly knowing resolution. \'\'The Jar\'\' is richer, more allegorical, and more fanciful. Don Lollo (Ciccio Ingrassia), a wealthy landowner, has produced such a prodigious olive crop that he orders an immense container for the oil. The jar, a terra cotta jug that is as big as a man, becomes Don Lollo\'s proudest possession. It stands in the middle of his courtyard until, one night, a shadow passes briefly over the face of the moon. When the shadow is gone, the jar is split in two. The story tells what happens when Don Lollo\'s glowering Uncle Dima (Franco Franchi), a man who likes to scare small boys by telling them he is the Devil\'s son, comes to fix the jug, and in the process seals himself up inside. The jar becomes a representation of Don Lollo\'s hold over the villagers, who must choose between saving Dima or preserving the Don\'s power. Like the other stories here, \'\'The Jar\'\' uses elements like the moon\'s influence, the sturdy, venerable architecture of Sicily and the unforgettable faces of some very well-chosen actors to heighten its spell. The fourth story, the briefest and most minor, is \'\'Requiem,\'\' about a village elder (Salvatore Rossi) who wishes to be buried in a particular spot, in defiance of the Baron (Pasquale Spadola) who owns the land. But \'\'Requiem\'\' serves a consolidating function, since it specifically recalls the opening scene (with the presence of the same actors) and anticipates the last. In the Epilogue, entitled \'\'Conversing With Mother,\'\' Luigi Pirandello (Omero Antonutti) returns to the same town that is seen in \'\'Requiem,\'\' and is visited by the apparition of his late mother (Regina Bianchi). She speaks of the importance of the departed, then tells a story of her own girlhood - one that lets \'\'Kaos\'\' end as it has begun, with a vision of strength, survival, and overwhelming natural beauty. \'\'Kaos,\'\' which is scheduled to open commercially sometime next month, will be seen tonight at 8 o\'clock, as the closing attraction of this year\'s New York Film Festival. KAOS, directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani; written by the Tavianis with the collaboration of Tonino Guerra, freely adapated from stories by Luigi Pirandello; director of photography, Giuseppe Lanci; edited by Roberto Perpignani; music by Nicola Piovani; produced by Giuliani De Negri; a RAI-Channel 1-Filmtre co-production; an MGM/UA Classics Release. At Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center, as part of the 23d New York Film Festival. Running time: 188 minutes. This film is rated R. THE OTHER SON The MotherMargarita Lozano The DoctorCarlo Cartier MOON SICKNESS BataClaudio Bigagli SaroMassimo Bonetti SidoraEnrica Maria Modugno The MotherAnna Malvica THE JAR Zi DimaFranco Franchi Don LolloCiccio Ingrassia REQUIEM SalvatoreBiagio Barone The PatriarchSalvatore Rossi Padre SarsoFranco Scaldati BaronPasquale Spadola CONVERSING WITH MOTHER Luigi PirandelloOmero Antonutti The MotherRegina Bianchi Kaos è il decimo film diretto dai fratelli Taviani ed è l\'ultimo film interpretato da Franco e Ciccio. È tratto da quattro Novelle per un anno di Pirandello, a cui si aggiunge un quinto racconto immaginato dai propri registi, ma ispirato dalle novelle Una giornata (Colloquio con la madre), e Colloquii coi personaggi (seconda parte). Iniziano la loro collaborazione con il direttore della fotografia Giuseppe Lanci (girano insieme cinque film di seguito, l\'ultimo essendo Tu ridi). Indice 1 Titolo2 Sinopsi3 Premi e riconoscimenti4 Differenze tra libro e film5 Note6 Bibliografia7 Collegamenti esterni Titolo È tratto da una citazione di Pirandello stesso: \"Io [...] sono figlio del Caos; e non allegoricamente, ma in giusta realtà, perché son nato in una nostra campagna, che trovasi presso ad un intricato bosco denominato, in forma dialettale, Càvusu dagli abitanti di Girgenti (Agrigento), corruzione dialettale del genuino e antico vocabolo greco Kaos\". Sinopsi Il film si svolge in quattro episodi e un epilogo. Filo comune che collega gli episodi è un corvo nero che si libra sopra la Sicilia di Pirandello con un campanello appeso al collo. L\'altro figlio racconta l\'odio di una madre nei confronti di uno dei suoi figli, il cui preoccupante aspetto sembra essere la reincarnazione vivente dell\'uomo che l\'ha violentata.Mal di luna mostra l\'amore, l\'angoscia e il desiderio di una giovane sposa, Sidora, di fronte alla malattia sconosciuta di suo marito Bata. Quest\'ultimo, infatti, nelle notti di luna piena è colto da raptus violenti e incontrollabili ...La giara presenta un proprietario terriero che fa riparare una costosa giara da un esperto artigiano, ma questi ne rimarrà bloccato all\'interno (il racconto è interpretato da Franco e Ciccio).Requiem descrive la lotta dei contadini contro gli amministratori di Ragusa che non permettono di seppellire il patriarca sui loro altipiani invece che nel lontano cimitero della città.Epilogo: colloquio con la madre, girato tra Lipari e l\'isola di Salina [1], mostra Pirandello parlante al fantasma di sua madre su di una storia che avrebbe voluto, ma non ha potuto, scrivere perché gli mancavano le parole. Premi e riconoscimenti 1985 - David di Donatello Migliore sceneggiatura a Paolo e Vittorio Taviani e Tonino GuerraMiglior produttore a Giuliani G. De NegriNomination Miglior film a Paolo e Vittorio TavianiNomination Miglior regista a Paolo e Vittorio TavianiNomination Migliore fotografia a Giuseppe LanciNomination Miglior colonna sonora a Nicola PiovaniNomination Migliore scenografia a Francesco BronziNomination Migliori costumi a Lina Nerli TavianiNomination Miglior montaggio a Roberto Perpignani 1985 - Nastro d\'argento Migliore sceneggiatura a Paolo e Vittorio Taviani e Tonino Guerra 1985 - Globo d\'oro Miglior film a Paolo e Vittorio Taviani Differenze tra libro e film Più volte i fratelli Taviani prendono certe libertà nell\'adattamento cinematografico del testo pirandelliano originale, senza però tradirne l\'essenza (vedere a modo d\'esempio la fine di Requiem), cioè l\'amore della terra e la lotta contro la fatalità. L\'esempio più notevole è l\'ultimo episodio del film, Colloquio con la madre, dove, oltre la malinconia dei ricordi, la ragione di vivere sradica in un affetto filiale che non dipende dalla presenza fisica della persona amata, e nello sfruttare ogni attimo di bellezza che ci si presenta. Anyone seriously hoping that this is a review of a Maxwell Smart movie might as well skip to the next article right now. Kaos is an Italian film by the Taviani brothers, an anthology film based on stories by Luigi Pirandello. The hallmarks of the film are sensitivity and observation. The Taviani brothers, barring Fellini, may be the finest Italian filmmakers still active (Olmi is right up there, too), and, while Kaos may not be their best work, it is a rich, representative film of their style: realistic, careful and caring, deeply felt. Italian film has a tradition of tending towards either the starkly realistic or the weirdly fantastic. The Taviani brothers have always preferred an understated realism to the flamboyant grotesqueries of Fellini or the angry myths of Pasolini. Their earlier films, like Padre, Padrone and The Night of the Shooting Stars have focussed on simply country people and their problems, particularly those imposed on them by the outside world. Kaos draws on Pirandello\'s stories of peasants in his native Sicily. Pirandello is an apt source for the Tavianis, as he shares their concern and admiration for the poor, especially the rural poor. Kaos is composed of a brief prologue, four separate stories, and an epilogue, all set in Sicily around the turn of the century. Except for a link from the prologue to the first story, and some common elements with the epilogue, each story is independent. The first story is about an old woman whose sons have gone to America. Illiterate, she has had neighbors write letters to them for fifteen years, but they never respond. Meanwhile, her other son labors hard and wants to provide a home for his mother, but she shuns him. In the course of the story, we discover why. The second story concerns a woman who recently married a man, only to find out that each month, on the night of the full moon, he becomes violently insane. An arrangement is made to have her mother and male cousin stay with her on the next full moon. However, the woman really wanted to marry the cousin, and still yearns for him, and he for her. The third story tells of a rich landowner who commissions a local potter to repair a huge jar which has been broken. The potter inadvertently seals himself inside, and the landowner, for whom the jar is a pride and joy, refuses to allow him to break it again. This story is a typical tale of peasant cunning versus wealth and power. The fourth tale also pits the peasant against the rich and their agents. A group of herders who have formed a village on the land of a wealthy noble years later decide that they must have their own cemetery up in the mountains where they live. The noble regards them as little better than squatters, and refuses their request. Again, the guile of the poor is matched against the force available to the rich. Finally, in the epilogue, Pirandello returns, an old man, to his mother\'s house. The shade of his mother appears, and tells him again of an episode from her childhood, when she and her siblings were forced to flee from Sicily to Malta. This episode is rich with echos of a past which cannot be recaptured, even by Pirandello\'s pen. The first episode is excellent, the second very good, the third good, and the fourth no better than fair. The epilogue is hard to judge objectively, as it is presented after one has already sat through two and a half hours of stories. The Tavianis certainly aren\'t typical Hollywood directors, and are willing to linger over a moment which they consider important, even if it slows the story down a bit. In their earlier films, which were of more usual length, this trait was a strength. Here, while it registers well in the early parts of the film, by the end one wishes for a little Spielbergian zip. Probably this film would be both better and more popular if one of the episodes were removed. (In fact, the Taviani brothers themselves suggested dropping an episode for the American release.) The acting is first rate, by a cast not likely to be familiar outside of Italy. (Or, for all I know, inside of Italy, either. The Taviani brothers have a reputation for working with unknown actors and non-actors.) The faces are distinctively Italian, without being Fellini grotesques. All of the performers seem effortlessly at home in the seared fields and rough homes of Sicily. The photography is typical of Taviani films. They favor fairly long takes, usually with rather static actions within the frame. Camera moves tend to be economical. They use action and movement to underline the important points, rather than to dazzle. The settings are humble and the Tavianis have wisely chosen not to make them any more glamorous or beautiful than they really are. Fields are generally dry and filled with stones. Homes often have dirt floors. Shadows exist because lighting is sparse, not because the cinematographer wanted to etch a face with patterns of dark and light. The photography in Kaos is a fine example of the restraint of individual virtuosity in favor of the overall good of the film. The cinematographer is given his reward in the epilogue, which is set largely on an island surrounded by an incredibly blue sea. Here, he is able to let loose with some really beautiful shots. Kaos is certainly not a film for everyone. It is almost undeniably too long, and drags in spots. While Kaos has fine moments of horror, humor, and mystery, these are not its main business. Of course, it is in Italian, with subtitles, which rules out a major segment of the filmgoing public, right there. The audience for Kaos is composed of people who are interested in films about people, not necessarily the people that they live with and know, but people who are obviously and undeniably real. Kaos has major rewards for that audience, and should not be missed by those who number themselves among it. Paolo and Vittorio Taviani (Italian pronunciation: [ˈpaːolo, vitˈtɔːrjo taˈvjaːni]; born 8 November 1931 and 20 September 1929 respectively) are noted Italian film directors and screenwriters. They are brothers, who have always worked together, each directing alternate scenes. Paolo Taviani\'s wife Lina Nerli Taviani has been costume designer of many of their films. At the Cannes Film Festival the Taviani brothers won Palme d\'Or and the FIPRESCI prize for Padre padrone in 1977 and Grand Prix du Jury for La notte di San Lorenzo (The Night of the Shooting Stars, 1982). In 2012 they reached again the top prize in a major festival, winning the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival with Caesar Must Die. Contents 1 Career2 Filmography 2.1 As film directors 2.1.1 1950s–1960s2.1.2 1970s–1980s2.1.3 1990s2.1.4 2000s2.2 As screenwriters 2.2.1 1950s–1960s2.2.2 1970s–1980s2.2.3 Since the 1990s2.3 Soundtrack composers 2.3.1 For their first eight films2.3.2 Nicola Piovani2.4 Favourite classical composers3 Awards4 References5 External links Career Both born in San Miniato, Tuscany, Italy, the Taviani brothers began their careers as journalists. In 1960 they came to the world of cinema directing, with Joris Ivens the documentary L\'Italia non è un paese povero (Italy is not a poor country), and they went on to direct two films with Valentino Orsini Un uomo da bruciare (1962) and I fuorilegge del matrimonio (1963). Their first autonomous film was I sovversivi (The Subversives, 1967), with which they anticipated the events of 1968. With actor Gian Maria Volonté they gained attention with Sotto il segno dello scorpione (Under the Sign of Scorpio, (1969) where one can see the echoes of Brecht, Pasolini and Godard. In 1971 they co-signed the media campaign against Milan\'s police commissioner Luigi Calabresi, published in the magazine L\'espresso. The revolutionary theme is present both in San Michele aveva un gallo (1971), an adaptation of Tolstoy\'s novel The Divine and the Human, a film greatly appreciated by critics, and in the film Allonsanfan (1974), in which Marcello Mastroianni has a role as an ex-revolutionary who has served a long term in prison and now views his idealistic youth in a much more realistic light, and nevertheless gets entangled in a new attempt in which he no longer believes. Their next film Padre padrone (1977) (Palme d\'Or at the Cannes Film Festival), taken from a novel by Gavino Ledda, speaks of the struggle of a Sardinian shepherd against the cruel rules of his patriarchal society. In Il prato (1979) there are nonrealistic echoes, while La notte di San Lorenzo (Saint Lorenzo\'s night) (1982) narrates, in a fairy-tale tone, a marginal event in the days before the end of World War II, in Tuscany, as seen through the eyes of some village people. The film was awarded the Special Jury Award in Cannes. Kaos (1984)—another literary adaptation—is a poignantly beautiful and poetical film in episodes, taken from Luigi Pirandello\'s Short Stories for a year. In Il sole anche di notte (1990) the Taviani brothers transposed in 18th century Naples the story from Tolstoy\'s \"Father Sergius\". Paolo Taviani and Vittorio Storaro From then onwards, the Taviani\'s inspiration proved faltering. Successes like Le affinità elettive, (1996, from Goethe) and an attempt to woo the international audiences like Good morning Babilonia, (1987), on the pioneers of cinema history, alternate with lesser films like Fiorile (1993) and Tu ridi (1996), inspired by the characters and short stories of Pirandello. In the 2000s, the two brothers turned successfully to directing television films and miniseries. They gave a respectful adaptation of Tolstoy\'s Resurrection (2001) and Luisa Sanfelice (2004) a sort of romantic-popular ballad from a book by Alexandre Dumas. Literary adaptations continue with La masseria delle allodole (2007), presented at the Berlin Film Festival in the section \'Berlinale Special\'. Their film Caesar Must Die won the Golden Bear at the 62nd Berlin International Film Festival in February 2012.[1] The film was also selected as the Italian entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards, but it did not make the final shortlist.[2] Filmography As film directors 1950s–1960s San Miniato, luglio \'44 (1954)L\'Italia non è un paese povero (with Joris Ivens, 1960)Un uomo da bruciare (together with Valentino Orsini, 1962)I fuorilegge del matrimonio (with Valentino Orsini, 1963)I sovversivi (1967)Sotto il segno dello scorpione (1969) 1970s–1980s San Michele aveva un gallo (1972)Allonsanfàn (1974)Padre Padrone (1977)Il prato (1979)La notte di San Lorenzo (1982)Kaos (1984)Good Morning, Babylon (1987) 1990s Il sole anche di notte (1990)Fiorile (1993)Le affinità elettive (1996)Tu ridi (1998) 2000s Un altro mondo è possibile (2001)Resurrezione (TV film, 2001)Luisa Sanfelice (TV miniseries, 2004)La masseria delle allodole (2007)Caesar Must Die (2012)Wondrous Boccaccio (2015) As screenwriters 1950s–1960s San Miniato, luglio \'44 (with Valentino Orsini and Cesare Zavattini, 1954)Un uomo da bruciare (with Valentino Orsini, 1962)I fuorilegge del matrimonio (with Lucio Battistrada, Giuliani G. De Negri, Renato Niccolai and Valentino Orsini, 1963)I sovversivi (1967)Sotto il segno dello scorpione (1969) 1970s–1980s San Michele aveva un gallo (based on a story by Tolstoy, 1972)Allonsanfàn (1973)Padre padrone (based on a book by Gavino Ledda, 1977)Il prato (with Gianni Sbarra, 1979)La notte di San Lorenzo (with Giuliani G. De Negri and Tonino Guerra, 1982)Kaos (based on short stories by Pirandello, 1984)Good Morning, Babylon (with Tonino Guerra, 1987) Since the 1990s Il sole anche di notte (with Tonino Guerra, 1990)Fiorile (with Sandro Petraglia, 1993)Le affinità elettive (based on a novella by Goethe, 1996)Tu ridi (based on short stories by Pirandello, 1998)Resurrezione (based on a novel by Tolstoy, 2001)Luisa Sanfelice (based on a novel by Alexandre Dumas, père, 2004) Soundtrack composers For their first eight films In chronological order: Gianfranco Intra: Un uomo da bruciareGiovanni Fusco: I fuorilegge del matrimonio, I sovversiviVittorio Gelmetti: Sotto il segno dello scorpioneBenedetto Ghiglia: San Michele aveva un galloEnnio Morricone: AllonsanfanEgisto Macchi: Padre padroneEnnio Morricone: Il prato Nicola Piovani Nicola Piovani their favourite composer: eight films together, from La notte di San Lorenzo to Luisa Sanfelice; a series only interrupted for Le affinità elettive (music by Carlo Crivelli). Favourite classical composers Mozart Adagio from Mozart\'s Clarinet Concerto in Padre padroneCavatina L\'ho perduta from Nozze di Figaro in KaosWagner: Baritone aria O du mein holder Abendstern from the 3rd act of Tannhauser in Notte di San LorenzoRossini: Sinfonia from Guglielmo Tell (Good Morning Babilonia)Aria dei gatti (Tu ridi)Chopin and Tchaikovsky in Resurrezione Awards 1977: Palme d\'or at Cannes Film Festival for Padre Padrone - Father and Master.1977: Grand Prix for Padre Padrone - Father and Master, Berlin International Film Festival1978: Special David di Donatello for Padre Padrone - Father and Master.1982: Grand Prix at Cannes Film Festival for The Night of the Shooting Stars.1983: David di Donatello for Best Film and David di Donatello for Best Director for The Night of the Shooting Stars.1984: Italian Golden Globes Golden Globe for Best Film for The Night of the Shooting Stars.1985: Italian Golden Globes Golden Globe for Best Film for Kaos.1985: David di Donatello for Best Script for Kaos.1986: Leone d\'Oro (Golden Lion) Life Career of the Venice International Film Festival.2002: Golden St. George at the 24th Moscow International Film Festival for Resurrection[3]2005: Italian Golden Globes Career Prize2007: Efebo d\'oro for La Masseria delle Allodole.2008: Laurea Honoris Causa in \"Cinema, Theatre and Multimedia Production\" by the Faculty of Literature and Philosophy of the University of Pisa.2012: Golden Bear and Prize of the Ecumenical Jury - Berlin International Film Festival for Caesar Must Die.2012: David di Donatello for Best Film and David di Donatello for Best Director for Caesar Must Die. Luigi Pirandello (Italian: [luˈiːdʒi piranˈdɛllo]; 28 June 1867 – 10 December 1936) was an Italian dramatist, novelist, poet and short story writer. He was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature for his \"bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage\". Pirandello\'s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and about 40 plays, some of which are written in Sicilian. Pirandello\'s tragic farces are often seen as forerunners of the Theatre of the Absurd. Contents 1 Biography 1.1 Early life1.2 Higher education1.3 Marriage1.4 Family disaster1.5 First World War1.6 Italy under the Fascists2 Selected works 2.1 Major plays2.2 Novels2.3 Short stories2.4 Poetry2.5 English Translations3 References4 Further reading5 External links Biography Early life Pirandello was born into an upper-class family in a village with the curious name of u Càvusu (Chaos), a poor suburb of Girgenti (Agrigento, a town in southern Sicily). His father, Stefano, belonged to a wealthy family involved in the sulphur industry, and his mother, Caterina Ricci Gramitto, was also of a well-to-do background, descending from a family of the bourgeois professional class of Agrigento. Both families, the Pirandellos and the Ricci Gramittos, were ferociously anti-Bourbon and actively participated in the struggle for unification and democracy (\"Il Risorgimento\"). Stefano participated in the famous Expedition of the Thousand, later following Garibaldi all the way to the battle of Aspromonte, and Caterina, who had hardly reached the age of thirteen, was forced to accompany her father to Malta, where he had been sent into exile by the Bourbon monarchy. But the open participation in the Garibaldian cause and the strong sense of idealism of those early years were quickly transformed, above all in Caterina, into an angry and bitter disappointment with the new reality created by the unification. Pirandello would eventually assimilate this sense of betrayal and resentment and express it in several of his poems and in his novel The Old and the Young. It is also probable that this climate of disillusion inculcated in the young Luigi the sense of disproportion between ideals and reality which is recognizable in his essay on humorism (L\'Umorismo). L\'Umorismo, 1908 Pirandello received his elementary education at home but was much more fascinated by the fables and legends, somewhere between popular and magic, that his elderly servant Maria Stella used to recount to him than by anything scholastic or academic. By the age of twelve he had already written his first tragedy. At the insistence of his father, he was registered at a technical school but eventually switched to the study of the humanities at the ginnasio, something which had always attracted him. In 1880, the Pirandello family moved to Palermo. It was here, in the capital of Sicily, that Luigi completed his high school education. He also began reading omnivorously, focusing, above all, on 19th-century Italian poets such as Giosuè Carducci and Arturo Graf. He then started writing his first poems and fell in love with his cousin Lina. During this period the first signs of serious contrast between Luigi and his father began to develop; Luigi had discovered some notes revealing the existence of Stefano\'s extramarital relations. As a reaction to the ever-increasing distrust and disharmony that Luigi was developing toward his father, a man of a robust physique and crude manners, his attachment to his mother would continue growing to the point of profound veneration. This later expressed itself, after her death, in the moving pages of the novella Colloqui con i personaggi in 1915. His romantic feelings for his cousin, initially looked upon with disfavour, were suddenly taken very seriously by Lina\'s family. They demanded that Luigi abandon his studies and dedicate himself to the sulphur business so that he could immediately marry her. In 1886, during a vacation from school, Luigi went to visit the sulphur mines of Porto Empedocle and started working with his father. This experience was essential to him and would provide the basis for such stories as Il Fumo, Ciàula scopre la Luna as well as some of the descriptions and background in the novel The Old and the Young. The marriage, which seemed imminent, was postponed. Pirandello then registered at the University of Palermo in the departments of Law and of Letters. The campus at Palermo, and above all the Department of Law, was the centre in those years of the vast movement which would eventually evolve into the Fasci Siciliani. Although Pirandello was not an active member of this movement, he had close ties of friendship with its leading ideologists: Rosario Garibaldi Bosco, Enrico La Loggia, Giuseppe De Felice Giuffrida and Francesco De Luca.[1] Higher education In 1887, having definitively chosen the Department of Letters, he moved to Rome in order to continue his studies. But the encounter with the city, centre of the struggle for unification to which the families of his parents had participated with generous enthusiasm, was disappointing and nothing close to what he had expected. \"When I arrived in Rome it was raining hard, it was night time and I felt like my heart was being crushed, but then I laughed like a man in the throes of desperation.\"[citation needed] Pirandello, who was an extremely sensitive moralist, finally had a chance to see for himself the irreducible decadence of the so-called heroes of the Risorgimento in the person of his uncle Rocco, now a greying and exhausted functionary of the prefecture who provided him with temporary lodgings in Rome. The \"desperate laugh\", the only manifestation of revenge for the disappointment undergone, inspired the bitter verses of his first collection of poems, Mal Giocondo (1889). But not all was negative; this first visit to Rome provided him with the opportunity to assiduously visit the many theatres of the capital: Il Nazionale, Il Valle, il Manzoni. \"Oh the dramatic theatre! I will conquer it. I cannot enter into one without experiencing a strange sensation, an excitement of the blood through all my veins...\" Because of a conflict with a Latin professor, he was forced to leave the University of Rome and went to Bonn with a letter of presentation from one of his other professors. The stay in Bonn, which lasted two years, was fervid with cultural life. He read the German romantics, Jean Paul, Tieck, Chamisso, Heinrich Heine and Goethe. He began translating the Roman Elegies of Goethe, composed the Elegie Boreali in imitation of the style of the Roman Elegies, and he began to meditate on the topic of humorism by way of the works of Cecco Angiolieri. In March 1891 he received his doctorate in Romance Philology[2] with a dissertation on the dialect of Agrigento: Sounds and Developments of Sounds in the Speech of Craperallis. Marriage After a brief sojourn in Sicily, during which the planned marriage with his cousin was finally called off, he returned to Rome, where he became friends with a group of writer-journalists including Ugo Fleres, Tomaso Gnoli, Giustino Ferri and Luigi Capuana. Capuana encouraged Pirandello to dedicate himself to narrative writing. In 1893 he wrote his first important work, Marta Ajala, which was published in 1901 as l\'Esclusa. In 1894 he published his first collection of short stories, Amori senza Amore. He married in 1894 as well. Following his father\'s suggestion he married a shy, withdrawn girl of a good family of Agrigentine origin educated by the nuns of San Vincenzo: Antonietta Portulano. The first years of matrimony brought on in him a new fervour for his studies and writings: his encounters with his friends and the discussions on art continued, more vivacious and stimulating than ever, while his family life, despite the complete incomprehension of his wife with respect to the artistic vocation of her husband,[citation needed] proceeded relatively tranquilly with the birth of two sons (Stefano and Fausto) and a daughter (Lietta). In the meantime, Pirandello intensified his collaborations with newspaper editors and other journalists in magazines such as La Critica and La Tavola Rotonda in which he published, in 1895, the first part of the Dialoghi tra Il Gran Me e Il Piccolo Me. In 1897 he accepted an offer to teach Italian at the Istituto Superiore di Magistero di Roma, and in the magazine Marzocco he published several more pages of the Dialoghi. In 1898, with Italo Falbo and Ugo Fleres, he founded the weekly Ariel, in which he published the one-act play L\'Epilogo (later changed to La Morsa) and some novellas (La Scelta, Se...). The end of the 19th century and the beginnings of the 20th were a period of extreme productivity for Pirandello. In 1900, he published in Marzocco some of the most celebrated of his novellas (Lumie di Sicilia, La Paura del Sonno...) and, in 1901, the collection of poems Zampogna. In 1902 he published the first series of Beffe della Morte e della Vita and his second novel, Il Turno. Family disaster The year 1903 was fundamental to the life of Pirandello. The flooding of the sulphur mines of Aragona, in which his father Stefano had invested not only an enormous amount of his own capital but also Antonietta\'s dowry, precipitated the collapse of the family. Antonietta, after opening and reading the letter announcing the catastrophe, entered into a state of semi-catatonia and underwent such a psychological shock that her mental balance remained profoundly and irremediably shaken. Pirandello, who had initially harboured thoughts of suicide, attempted to remedy the situation as best he could by increasing the number of his lessons in both Italian and German and asking for compensation from the magazines to which he had freely given away his writings and collaborations. In the magazine New Anthology, directed by G. Cena, meanwhile, the novel which Pirandello had been writing while in this horrible situation (watching over his mentally ill wife at night after an entire day spent at work) began appearing in episodes. The title was Il Fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal). This novel contains many autobiographical elements that have been fantastically re-elaborated. It was an immediate and resounding success. Translated into German in 1905, this novel paved the way to the notoriety and fame which allowed Pirandello to publish for the more important editors such as Treves, with whom he published, in 1906, another collection of novellas Erma Bifronte. In 1908 he published a volume of essays entitled Arte e Scienza and the important essay L\'Umorismo, in which he initiated the legendary debate with Benedetto Croce that would continue with increasing bitterness and venom on both sides for many years. In 1909 the first part of I Vecchi e I Giovani was published in episodes. This novel retraces the history of the failure and repression of the Fasci Siciliani in the period from 1893 to 1894. When the novel came out in 1913 Pirandello sent a copy of it to his parents for their fiftieth wedding anniversary along with a dedication which said that \"their names, Stefano and Caterina, live heroically.\" However, while the mother is transfigured in the novel into the otherworldly figure of Caterina Laurentano, the father, represented by the husband of Caterina, Stefano Auriti, appears only in memories and flashbacks, since, as was acutely observed by Leonardo Sciascia, \"he died censured in a Freudian sense by his son who, in the bottom of his soul, is his enemy.\" Also in 1909, Pirandello began his collaboration with the prestigious journal Corriere della Sera in which he published the novellas Mondo di Carta (World of Paper), La Giara, and, in 1910, Non è una cosa seria and Pensaci, Giacomino! (Think it over, Giacomino!) At this point Pirandello\'s fame as a writer was continually increasing. His private life, however, was poisoned by the suspicion and obsessive jealousy of Antonietta who began turning physically violent. In 1911, while the publication of novellas and short stories continued, Pirandello finished his fourth novel, Suo Marito, republished posthumously (1941), and completely revised in the first four chapters, with the title Giustino Roncella nato Boggiòlo. During his life the author never republished this novel for reasons of discretion; within are implicit references to the writer Grazia Deledda. But the work which absorbed most of his energies at this time was the collection of stories La Vendetta del Cane, Quando s\'è capito il giuoco, Il treno ha fischiato, Filo d\'aria and Berecche e la guerra. They were all published from 1913–1914 and are all now considered classics of Italian literature. First World War As Italy entered the First World War, Pirandello\'s son Stefano volunteered for service and was taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarians. In 1916 the actor Angelo Musco successfully recited the three-act comedy that the writer had extracted from the novella Pensaci, Giacomino! and the pastoral comedy Liolà. In 1917 the collection of novellas E domani Lunedì (And Tomorrow, Monday...) was published, but the year was mostly marked by important theatrical representations: Così è (se vi pare) (Right you are (if you think so)), A birrita cu\' i ciancianeddi and Il Piacere dell\'onestà (The Pleasure Of Honesty). A year later, Ma non è una cosa seria (But It\'s Nothing Serious) and Il Gioco delle parti (The Game of Roles) were all produced on stage. Pirandello\'s son Stefano returned home when the war ended. Bust of Pirandello in a public park in Palermo In 1919 Pirandello had his wife placed in an asylum.[citation needed] The separation from his wife, toward whom, despite her moroffer jealousies and hallucinations, he continued to feel a very strong attraction, caused great suffering for Pirandello who, even as late as 1924, believed he could still properly care for her at home. She never left the asylum. 1920 was the year of comedies such as Tutto per bene, Come prima meglio di prima, and La Signora Morli. In 1921, the Compagnia di Dario Niccomedi staged, at the Valle di Roma, the play, Sei personaggi in cerca d\'autore, Six Characters in Search of an Author. It was a clamorous failure. The public divided into supporters and adversaries, the latter of whom shouted, \"Asylum, Asylum!\" The author, who was present at the performance with his daughter Lietta, left through a side exit to avoid the crowd of enemies. The same drama, however, was a great success when presented in Milan. In 1922 in Milan, Enrico IV was performed for the first time and was acclaimed universally as a success. Pirandello\'s international reputation was developing as well. The Sei personaggi was performed in English in London and New York. Italy under the Fascists In 1925, Pirandello, with the help of Mussolini, assumed the artistic direction and ownership of the Teatro d\'Arte di Roma, founded by the Gruppo degli Undici. He described himself as \"a Fascist because I am Italian.\" For his devotion to Mussolini, the satirical magazine Il Becco Giallo used to call him P. Randello (randello in Italian means club).[3] His play, The Giants of the Mountain, has been interpreted as evidence of his realization that the fascists were hostile to culture; yet, during a later appearance in New York, Pirandello distributed a statement announcing his support of Italy\'s annexation of Abyssinia. He gave his Nobel Prize medal to the Fascist government to be melted down for the Abyssinia Campaign. Mussolini\'s support brought him international fame and a worldwide tour, introducing his work to London, Paris, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Germany, Argentina, and Brazil.[citation needed] He expressed publicly apolitical belief, saying \"I\'m apolitical, I\'m only a man in the world...\"[4] He had continuous conflicts with famous fascist leaders. In 1927 he tore his fascist membership card in pieces in front of the dazed secretary-general of the Fascist Party.[5] For the remainder of his life, Pirandello was always under close surveillance by the secret fascist police OVRA.[6] Pirandello\'s conception of the theatre underwent a significant change at this point. The idea of the actor as an inevitable betrayer of the text, as in the Sei personaggi, gave way to the identification of the actor with the character that she plays. The company took their act throughout the major cities of Europe, and the Pirandellian repertoire became increasingly well known. Between 1925 and 1926 Pirandello\'s last and perhaps greatest novel, Uno, Nessuno e Centomila (One, No one and One Hundred Thousand), was published serially in the magazine Fiera Letteraria. Pirandello was nominated Academic of Italy in 1929, and in 1934 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.[2] He was the last Italian playwright to be chosen for the award until 9 October 1997.[7][8] Pirandello died alone in his home at Via Bosio, Rome, on 10 December 1936.[9] Selected works Major plays 1916: Liolddfdà1917: Così è (se vi pare) (So It Is (If You Think So))1917: Il piacere dell\'onestà (The Pleasure of Honesty)1918: Il gioco delle parti (The Rules of the Game)1919: L\'uomo, la bestia e la virtù (The Man, the Beast and the Virtue)1921: Sei personaggi in cerca d\'autore (Six Characters In Search of an Author)1922: Enrico IV (Henry IV)1922: L\'imbecille (The Imbecile)1922: Vestire gli ignudi (Clothing The Naked)1923: L\'uomo dal fiore in bocca (The Man with the Flower In His Mouth)1923: La vita che ti diedi (The Life I Gave You)1924: Ciascuno a suo modo (Each In His Own Way)1927: Diana e la Tuda (Diana and Tuda)1930: Questa sera si recita a soggetto (Tonight We Improvise) Novels 1902: Il turno (The Turn)1904: Il fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal)1908: L\'esclusa (The Excluded Woman)1911: Suo marito (Her Husband)1913: I vecchi e i giovani (The Old and the Young)1925: Quaderni di Serafino Gubbio (Serafino Gubbio\'s Journals)1926: Uno, nessuno e centomila (One, No one and One Hundred Thousand) Short stories 1922–37: Novelle per un anno (Short Stories for a Year), 15 volumes Poetry 1889: Mal giocondo (Playful Evil)1891: Pasqua di Gea (Easter of Gea)1894: Pier Gudrò, 1809–18921895: Elegie renane, 1889–90 (Rheinland Elegies)1901: Zampogna (The Bagpipe)1909: Scamandro1912: Fuori di chiave (Out of Tune) English Translations Nearly all of Pirandello\'s works have been translated into English by the actor and playwright Robert Rietti. 3218

KAPPYSCOINS G7281 ISRAEL 1984 BROTHERHOOD SILVER PROOF 36th INDEPENDENCE DAY $29.99

Star Over Bethlehem Israel Crystal Paperweight Figurine -Gallery Originals 1984 $15.00

THE HOLY SCRIPTURES JEWISH BIBILE ACCORDING TO THE MASORETIC TEXT 1984 ISRAEL $10.42

VINTAGE 1984 ISRAEL HOLYLAND HAZOR MUSEUM BUILDING POSTCARD PALPHOT #7836 $3.99

VINTAGE 1984 ISRAEL HAZOR MUSEUM POSTCARD PALPHOT #2084 HILL EXCAVATIONS $3.99

VINTAGE 1984 ISRAEL HOLYLAND HAZOR MUSEUM POSTCARD PALPHOT #5264 CNAANITE ALTAR $3.99

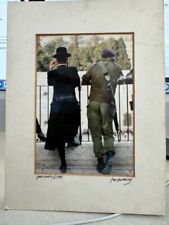

Jerusalem 1984 Photograph by Jodi Klinetsky $95.00

THE HOLY SCRIPTURES JEWISH BIBILE ACCORDING TO THE MASORETIC TEXT 1984 ISRAEL $29.99

|