|

On eBay Now...

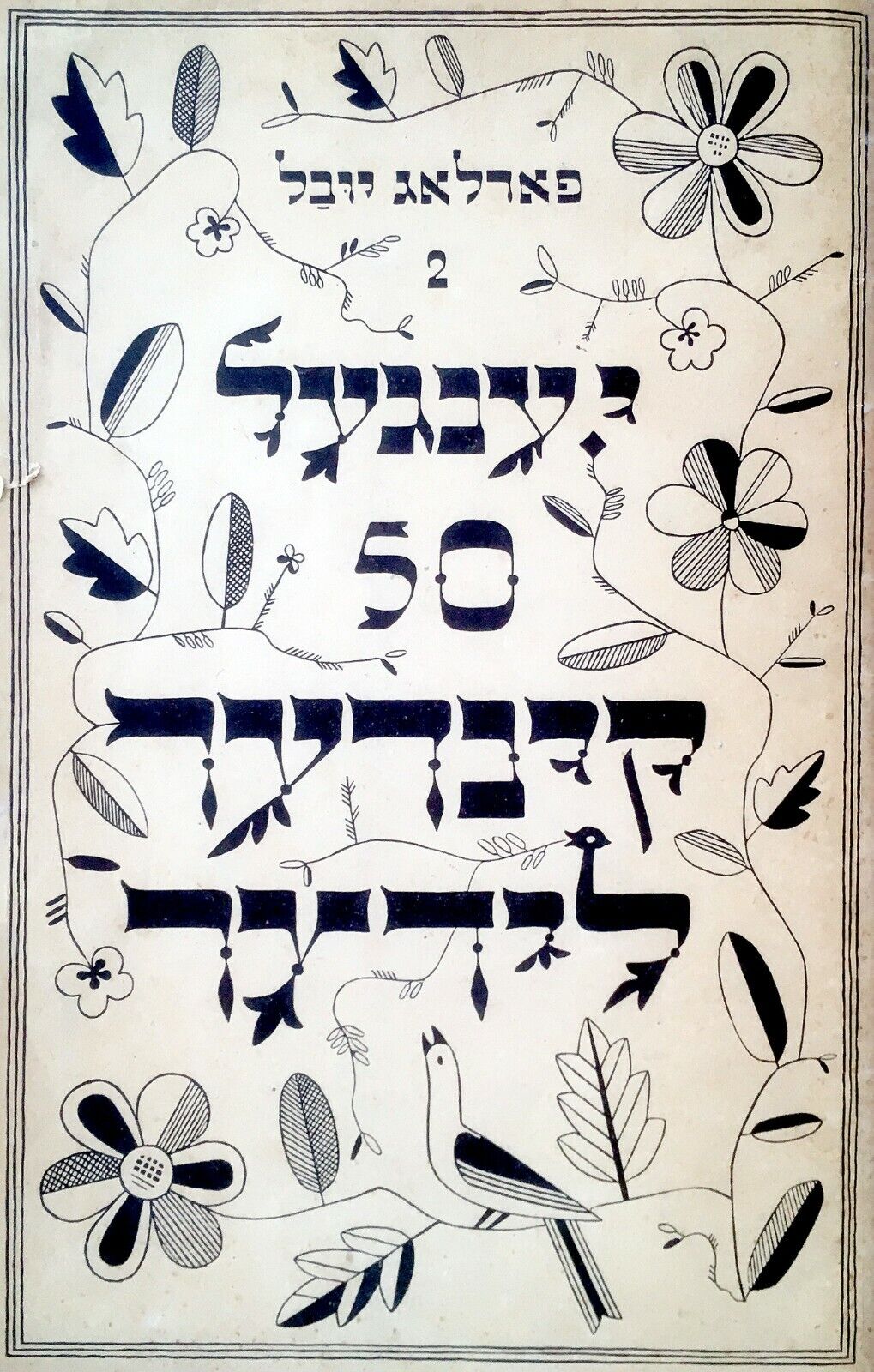

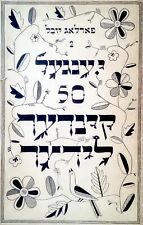

1923 Judaica SONG BOOK Yiddish RUSSIAN -ST. PETERSBURG SOCIETY JEWISH FOLK MUSIC For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1923 Judaica SONG BOOK Yiddish RUSSIAN -ST. PETERSBURG SOCIETY JEWISH FOLK MUSIC:

$164.50

DESCRIPTION : Up for sale is an EXTREMELY RARE , Almost 100 years old JEWISH - YIDDISH - RUSSIAN publication. It\'s a SONG BOOK for the JEWISH - YIDDISH SCHOOL and FAMILLY. The EXCITING BOOK holds in its 40 pages 50 songs , MUSICAL NOTES and LYRICS . These SONGS were mainly composed and arranged by the members of the RUSSIANST. PETERSBUR SOCIETY for JEWISH FOLK MUSIC. It\'s FIRST EDITION was published in Moscow Russia in 1916.This collection of JEWISH-YIDDISH- RUSSIAN SONGS was compiled and edited byJoel (or Yoel) Engel(Russian:Юлий Дмитриевич (Йоэль) Энгель,Yuliy Dmitrievich (Yoel) Engel. He was a Russian-Jewish COMPOSER , MUSIC CRITIC and pedagogue associated with theSociety for Jewish Folk MusicinSt. Petersburg.He was also the founder of the \"JUVAL\" musical publishing house. He conducted fieldwork in theRussian Empireto collect Jewish religious and secular music.Materials he collected were used in the compositions of such figures asJoseph Achron,Lev Pulver, andAlexander Krein.Published by \"JUVAL\" BERLIN in 1923 . Captures and text in YIDDISH ( Also in latin letters ) . Original Illustrated wrappers. 10.5\" x 6.5\". 40 pp. Very good condition. Used. Tightly bound. Somewhat fragile. A fewfragile pages were reinforced ( Pls look at scan foraccurate AS IS images ) .Will be sent inside a protective rigidpackaging .

AUTHENTICITY : Thisis anORIGINALvintage1923 ( Dated )copy, NOT a reproduction or a reprint orrecent edition,It holds a life long GUARANTEE forits AUTHENTICITY andORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS : Payment method accepted :Paypal& All credit cards.

SHIPPMENT : SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25 .Will be sent inside a protective packaging. Handling around 5-10 days after payment.The New Jewish School can be compared to other national currents, forming the European musical landscape since the middle of the 19th century. While Russian, Czech, Spanish or Norwegian national music was able to unfold and establish itself in the cultural conscience, the development of the Jewish school was violently terminated by the Stalinist and national-socialist policy after only three decades.The history of the New Jewish School started in the first decade of the 20th century. In 1908 theSociety for Jewish folk musicwas founded in St. Petersburg - the first Jewish musical institution in Russia. Important composers, such asJoseph Achron,Michail Gnesin,Alexander Krejn,Moshe Milner,Solomon Rosowsky,Lazare Saminskyand others joined it. In contrast to Jewish composers from Western Europe these young artists did not lose their connection to the Jewish community. The more than five million Jews in Russia (at that time about half of the Jews in the world) lived in old traditions, which remained a nurturing soil and a source of inspiration for musicians.Initially, the activities of the Society concentrated on the collection, processing, publication and presentation of Jewish folklore. At the same time more and more original compositions were created, which were published in its own publishing company. Additionally, concerts, lectures and ethnologic expeditions were organized.By 1913, the Society already had more than one thousand members; subsidiaries were opened in seven cities. For young composers (about twenty five of them) the Society was a union of kindred spirits, where discussions could be held and a familiar atmosphere prevailed.As a result of the political and economic collapse in the years 1918 to 1921, the Petersburg Society and its subsidiaries in other cities had to discontinue their work. Most of the leading members from Petersburg emigrated during this time, while the members in Moscow had smaller losses. This is why the center o f Jewish music re-located from Petersburg to Moscow in the 1920s. In Moscow the Society could be revived.David Schor, the first president of the newly formedSociety for Jewish music, stressed in a lecture, that in contrast to the previous Society for Jewish folk music, performances, expenses and spreading of Jewish art music would be the center of attention.It was clear from the beginning that the activity of the Society would not attain the same dimensions as its predecessor. Its activities concentrated predominantly on concerts. These concerts played a crucial role for the new Jewish music, as they offered the composers a platform which they normally would not have had. This was especially an important incentive for young composers to devote themselves to Jewish music. In the years 1923 to 1929 hundreds of works (for the most part chamber music), some of which were exclusively composed for the concerts of the Society, were created in this way. The programs were worked out by a music commission, which included, among others, the composersMichail Gnesin, the brothersGrigoriandAlexander KreinandAlexander Weprik.One can judge the high standard of the Society by looking at the names of the performers. First-class Jewish and Russian artists, like the pianist Maria Judina or the members of the famous Beethoven quartet remained linked with the Society throughout the entire time of its existence.Starting in 1925 the Society for Jewish music was attacked by music officials for its repertoire. Serious signs of a crisis became evident at the end of 1927. The Society was increasingly steered by communists. They demanded a complete re-orientation, especially a repertoire that met the requirements of Jewish working people. The days of most Jewish cultural institutions were already numbered - the last event of the society is dated December 22nd, 1929. Jewish artists had to adapt to the reigning cultural doctrine of socialist realism and had to deny their Judaism.But at that time the New Jewish School was no longer confined to Russia. It also had a considerable influence on international Jewish musical life. Just as its activities in Russia had almost come to a standstill, this music spread throughout Europe, with Vienna as the most outstanding center. In 1928 aSociety for the Promotion of Jewish Musicwas founded in Vienna. Its most important composers wereIsrael Brandmann,Joachim StutschewskyandJuliusz Wolfsohn.Not only was the New Jewish School a victim of Stalinist antisemitic politics in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, but in other countries too its development was thwarted more and more by antisemitism. The final end came with NS-domination over West- and Central Europe, leading to the expulsion and murder of Jewish musicians.******Joseph Achron (1886-1943) received violin lessons from his father when he was five years old. His father was an amateur violinist and recited prayers at the synagogue. When Achron was seven years old he began the career of a child prodigy with his first public appearance in Warsaw, followed by concerts in all parts of Russia. In 1899 he joined the class of the legendary violin teacher Leopold Auer at the Conservatory in Petersburg where he also studied composition under Anatoly Ljadov.He joined theSociety for Jewish Folk Musicin 1911 and from then on occupied himself in theory and practice with the Jewish music tradition. His first \"Jewish\" work \"Hebrew Melody\" became famous straightaway through the interpretation by Jascha Heifetz.In 1922 Achron went to Berlin, where he, together withMichail Gnesin, ran the Jewish music publishing company \"Jibneh\". In 1924 Achron spent some months in Palestine before he emigrated to America.Even though he achieved great success with his first violin concert (which he performed as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussewitzky) and the suite \"Golem\" for chamber orchestra (first performance at the 2. Festival of the International Society for New Music in Venice), he was unable to establish himself as a composer in the USA. Arnold Schönberg, a friend of Achron, described him in his obituary as \"one of the most underrated modern composers\". ****Michail Gnesin (1883-1957) came from the family of a rabbi. His three sisters founded a music institute in Moscow, which still exists under the name \"Gnesin Russian Academy of Music\". Gnesin himself taught composition there. Among his students were Aram Chatschaturjan and Tichon Chrennikow.In 1921 Gnesin traveled to Palestine, where he remained for almost one year. He lived there like a hermit in a remote guest house between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. There where he composed his opera \"Abraham\'s Youth\" based on old Jewish legends - the first Jewish national opera. This work was a kind of credo in which he answered the question about his artistic and human identity.In the mid 1920s Gnesin became chairman of theSociety for Jewish Music in Moscow. When the political pressure increased, Gnesin fought for the society\'s continued existence. He knew that he put himself in mortal danger, when he defended Jewish music against the discriminations. While masses of people were vanishing in Gulags, he still had the courage to support the freedom of art. After the society was forced to discontinue its work in 1930 and Jewish music was no longer allowed to exist in Russia, Gnesin offered passive resistance - he did not compose at all for a number of years. ****Alexander Krein (1883-1951) learned Jewish folk music as a child first hand. His father was a well-known Klezmer musician and folk poet. He played the violin at Jewish weddings and his children had to accompany him on zymbales. All of the seven Krein brothers later became musicians, some of them were even famous, such as the composerGrigori Kreinor the violinist David Krein.Alexander Krejn celebrated his biggest successes in the 1920s as a composer of stage music. In this way the performance of the play \"The night in the old market\" (after Izchak Leib Peretz) at the Jewish state theatre in Moscow (GOSET) became a triumph for the theatre as well as the composer. Even in Western Europe, where the theatre gave guest performances in 1927, the play was greeted with great enthusiasm.After Jewish music was banned in the Soviet Union, Krejn, in contrast toMichail Gnesin, adapted to the conditions. His ballet \"Laurentsia\", in which Krein used Spanish folklore, later achieved great popularity. This ballet has remained in the repertoire of many Russian theatres to this day.In comparison his most important work, the cantata \"Kaddish\", could not be performed at all. For decades Krein\'s score was considered as missing. Only a couple of years ago it was discovered that the score had been saved. The work was then performed in Russia and in the USA. *** Solomon Rosowsky (1878-1962) was the son of the famous cantor Baruch Leib Rosowsky of Riga. He began to study music only after his graduation from the University of Kiev, where he received a law degree. Among his teachers at the St. Petersburg Conservatory was Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov. Together with the pianist Leonid Nesvishsky (Arie Abilea), the singer Joseph Tomars, the composer Lazare Saminsky, and several other musicians Rosowsky organized theSociety for Jewish Folk Musicin 1908. In 1918 he became music director of the Jewish Art Theater (called later GOSET).Rosowsky returned to Riga in 1920 and founded the first Jewish Conservatory there. After a five-year stay, he left for Palestine, where at that time he at first was one of the few professional musicians. The folk music of Palestinian Jews became a major new inspiration for his compositions. Despite the enthusiastic work of the pioneers, the material living conditions in Palestine at that time were still extremely arduous. And for an artist who was used to the rich musical life of St. Petersburg, the land had little to offer in those early days except for a few amateur orchestras and two music schools. However, Rosowsky stayed on. He composed stage music for the workers\' theater \"Ohel\", gave lessons and began his path-breaking research into the music of the Bible, which later made his name known all over the world. He even tried, together with David Schor and David Mirenburg, to continue the concert activities of the New Jewish School, founding the music society \"Hanigun\".His latter years he spent in New York, where he taught at the Cantors\' Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary. His magnum opus, \"The Cantillation of the Bible: Five Books of Moses\", was published in 1957. **** Lazare Saminsky (1882-1959) had already studied Mathematics and Philosophy when he started his professional musical education - at the Conservatory in St. Petersburg with Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov and Anatoly Lyadov. In 1908 Saminsky was co-founder of theSt. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music. With a temperament typical for him he defended the importance of the old synagogue music in public discussions, articles and lectures. He regarded this music as an authentic part of Jewish music tradition and as a substantial basis for new Jewish music. His views were confirmed on his expeditions into the Caucasus (1913) where he researched the old liturgical music of the Jews.In the years 1919-1920 Saminsky emigrated via Jerusalem, Paris and London to the USA, which became his adoptive country. In the years that followed, his name became famous internationally. He was co-founder and chairman of the American League of Composers and had a brilliant career as a conductor. In 1925 he became musical director of New York\'s largest synagogue, theTemple Emanu-El, which thanks to Saminsky\'s artistic function evolved to a renowned center for Jewish music. **** Most biographies of Jewish artists of the twentieth century are marked by frequent changes of place, flight and expulsion. The life of Joachim Stutschewsky (1891-1982) was particularly restless. In his memoirs, he compares himself to a traveling Jewish musician – a klezmer who was never allowed to remain anywhere for long and was never able to find rest. Stutschewsky was quite familiar with the east European klezmer milieu from his own experience, since he was born into a well-known klezmer family in Ukraine. Like all family members for many generations, he began taking music lessons at a young age and then played in his father\'s klezmer ensembles.In 1909, Stutschewsky went to Leipzig to study cello withJulius Klengelat the conservatory. After finishing his studies, Stutschewsky first returned to Russia, but soon fled abroad once again to escape having to serve in the Russian military. Then he lived in Jena, where he began to play a large number of concerts as soloist and chamber musician. When the First World War broke out, he had to flee once again because he was a Russian citizen, and moved to Switzerland, where he organized the first concerts of Jewish folk and art music.He moved to Vienna in 1924 and together with Rudolf Kolisch founded the famous Vienna String Quartet, which won international renown with its premieres of works by composers in the New Vienna School founded by Arnold Schoenberg. In Vienna, Stutschewsky also continued his activities in the area of Jewish music as a composer, cellist, journalist and organizer. He was the spiritus rector of theSociety for the Promotion of Jewish Music.In 1938, shortly before the arrival of the German troops, he fled to Switzerland and emigrated that same year to Palestine, where at first he continued to perform concerts of new Jewish music as well as holding lectures throughout the country. From the 1950\'s on, he devoted himself nearly exclusively to composing. In his work, Stutschewsky unites the traditional Jewish idiom with a musical language that was often quite advanced. Elements of the folk music of Ashkenazi, Sephardic and Yemenite Jews from a wide variety of different countries who had now made their homes in Israel found their way into his compositions. **** Juliusz Wolfsohn (1880-1944) came from a well known Zionist family. His uncle, David Wolfsohn, was among the first Zionist leaders, later he became Theodor Herzl\'s successor as President of the World Zionist Organization. Juliusz Wolfsohn studied piano at the Conservatories of his home city, Warsaw, and in Moscow and then with Raoul Pugno in Paris and with Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna.Already in the early 1910s Wolfsohn began, without any connection to the activities in St. Petersburg, to collect and arrange Jewish folk songs. Until 1920 he composed 12 „Paraphrases on Old Jewish Folk Tunes“ for piano, which were printed in 3 volumes by Universal Edition, as well as a \"Jewish Rhapsody\" for piano, which was also based on Jewish folk themes.Together withJoachim Stutschewsky, Abram Dzimitrovsky andIsrael Brandmann, Wolfsohn was one of the protagonists of theSociety for the Promotion of Jewish Musicin Vienna; he moreover supported Jewish art music as a renowned music critic. His „Hebrew Suite“ for piano and orchestra, which was internationally performed in the 1930s, became his most successful composition. In 1939 Wolfsohn fled to the USA, he died in New York. ****Susman (Zinoviy Aronovich) Kiselgof(Зусман Аронович Кисельгоф,זוסמאַן קיסעלהאָף; 1878 – 1939) was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with theSociety for Jewish Folk MusicinSt. Petersburg.[1][2][3][4]Like his contempraryJoel Engel, he conducted fieldwork in theRussian Empireto collect Jewish religious and secular music.[5]Materials he collected were used in the compositions of such figures asJoseph Achron,Lev Pulver, andAlexander Krein.[5]Biography[edit]Kiselgof was born inVelizh,Vitebsk Governorate, Russian Empire, on March 15, 1878 (March 3 by theJulian Calendarthen in use).[6]He was the son of aMelamed.[2]He studied at aChederand then at the Velizh Jewish College and at the Vilna Jewish Teacher\'s College in 1894.[5]He never received a full musical education, but showed a natural ability to perceive pitch and learn new instruments. At age 11 he took violin lessons from aklezmernamed Meir Berson, but was otherwise mostly self-taught.[5][7]He began his efforts to collect Jewish folk music around 1902.[5]He also became a member of theGeneral Jewish Labour Bundand became involved in its educational efforts for some years, apparantly from 1898 to either 1906 or 1908.[2][6]He may have spent at least a few weeks in prison in 1899 for possession of illegal literature.[6]After teaching at various institutions inVitebsk, Kiselgof relocated toSaint Petersburgin 1906, where he became a teacher in the school of theSociety for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russiaand a choir conductor.[5]In 1908 he married his wife Guta Grigorievna.[6]He continued his efforts to document and research Jewish folklore; from 1907 to 1915 he made annual summer expeditions to thePale of Settlement, during which he recorded more than 2000 Jewish folk songs and tunes. His trip in 1907 was toMogilev Governorateto the center ofChabad Hasidism.[8]In 1913-14 he participated in the well-known ethnographic expeditions ofAn-sky. He also became very active in Jewish cultural life in St. Petersburg; in 1908, he was a founding member of theSociety for Jewish Folk Music, and was on its board until 1921.[5][7]In that group, he worked with such figures asLazare Saminsky,Mikhail Gnessin,Solomon Rosowsky, and Pavel Lvov.[7]And 1909, he was involved in fundraising efforts to create a new Jewish theatre in the city.[5]He also became a friend and tutor toJascha Heifetzduring this time.[7]In 1911, he published his best-known songbookLider-zamelbukh far der yidishe shul un familie(Song collection for the Jewish school and family), a collection of roughly 90 songs in choral arrangement with piano. These included secular and religious Yiddish songs and wordlessNigunim.[9]It was reprinted several times; the 1923 reprint isavailable in digital formatin the collection of theYiddish Book Center.In the early period of theSoviet Union, Kiselgof continued along the same music and education path he had already been on. In 1919, he became the musical consultant, teacher and choirmaster for the newly founded Petrograd Jewish Theater Studio of Alexei Granovsky (later known asGOSET).[5]In 1920 he became director of National Jewish School No.11 and Children\'s Home No.78 in Leningrad.[5]HisWax cylinderrecordings were also transferred from the Jewish Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg to the Institute of Proletarian Culture inKyiv.[8]Kiselgof was arrested in the summer of 1938 by theNKVD.[6]His wife Guta died in July 1938, shortly after his arrest.[6]Meanwhile his daughter wrote petitions toLavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD, asking for his release and the right to meet with him.[6]Kiselgof was released from prison on May 11, 1939, and died within a month due to poor health.[6][5]He was apparently buried in the Preobrazhénskoye Jewish cemetery in Saint Petersburg, although the location of his gravesite cannot be found.[6]Legacy[edit]A number of composers affiliated with theGOSETtheatre and theSociety for Jewish Folk Musicused folkloric materials collected by Kiselgof in their compositions. These includeJoseph Achronin his music for the playsThe SorceressandMazltov,Lev Pulverin the music forTwo Hundred ThousandandNight at the Rebbe\'s House, andAlexander Kreinin the music forAt Night at the Old Marketplace.[5]His original manuscripts, cylinders and materials were held in the Institute of Proletarian Jewish Culture during his lifetime, and upon its dissolution in 1949 were sent to theVernadsky National Library of Ukraine.[8]Some audio recordings from his expeditions can be purchased on CD from the Vernadsky Library or streamed from their website.[10]Some of those musical manuscripts are currently being digitized by a crowdsourced project organized by theKlezmer Institutecalled the Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project (KMDMP).[11]References[edit]^Nemtsov, Jascha (2009).Der Zionismus in der Musik: Jüdische Musik und nationale Idee. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p.154.ISBN9783447057349.^Jump up to:abcLoeffler, James Benjamin (2010).The most musical nation: Jews and culture in the late Russian empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp.159–61.ISBN9780300198300.^Walden, Joshua S. (January 2009). Review of Beate Schröder-Nauenburg,Der Eintritt des Jüdischen in die Welt der Kunstmusik.Journal of Jewish Identities. Issue 2, No. 1. pp. 85-87. Retrieved viaProject Musedatabase, 2018-07-08.doi:10.1353/jji.0.0000. Preview:[1](subscription required for full article).^Schröder-Nauenburg, Beate (2007).Der Eintritt des Jüdischen in die Welt der Kunstmusik. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.ISBN9783447056038. p.20.^Jump up to:abcdefghijklSholokhova, Lyudmila (2004). \"Zinoviy Kiselhof as a Founder of Jewish Musical Folklore Studies in the Russian Empire at the Beginning of the 20th Century.\". In Grözinger, Karl-Erich (ed.).Klesmer, Klassik, jiddisches Lied: jüdische Musikkultur in Osteuropa. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp.63–72.Mikhail \"Moshe\" Arnoldovich Milner(Мильнер, Михаил \"Моше\" Арнольдович; Rokitno Basilovsky,Kiev Governorate1886-Leningrad, 1953) was a Russian Jewish pianist and composer. He is notable as composer, and conductor, of the first Yiddish opera in post-revolution Russia \"Die Himlen brenen\" (\"The Heavens Burn\") in 1923.[1][2][3]He sang in the choir of theBrodsky Choral Synagoguein Kiev, then attended theKiev Conservatory. He studied at theSt. Petersburg Conservatoryfrom 1907 till 1915. While in St Petersburg Milner began to composeYiddish songsforSusman Kiselgof(Зусман Кисельгоф)\'sSociety for Jewish Folk Music(Общество еврейской народной музыки).[4]He also wrote incidental music for Jewish theaters. He provided music for theHabima TheaterandState Jewish Theater, Moscow(GOSET) (Государственный еврейский театр (ГОСЕТ)), and the Leningrad choirEvokans(Евоканс). ****МИЛЬНЕР Моше Михаэль (Михаил Арнольдович) у. Киевской губ. – 1953,Ленинград), композитор, дирижер, хормейстер. С десятилетнего возраста пел в хоре Я.-Ш.Мороговского, затем в Киевской хоральной синагоге. Учился игре на фп. у рук. хора этой синагоги А.Н.Дзмитровского и у О.Д.Веккер. В 1907–15 учился в Петерб. (Петрогр.) конс. по кл. комп. у А.К.Лядова, Я.Витола, М.О.Штейнберга, В.П.Калафати. Был чл. Об-ва еврейской нар. музыки (осн. в 1908), в числе первых изд. к-рого опубл. его фп. пьеса «У ребе на проводах Царицы-субботы» (1914). М. дирижировал хорами этого об-ва (1911–23), Петерб. Большой синагоги (1912–19), а также воен. орк. (1915–18). В 1924–25 зав. муз. частью Моск. еврейского т-ра, к драм, спектаклям к-рого (а также для студии «Габима») писал музыку (более чем к 40 спектаклям). В 1923–31 работал в Харьковском еврейском т-ре (с 1929 – зав. муз. частью). В 1931–41 рук. еврейского вок. анс. «Евоканс» вЛенинграде, в годы войны 1941–45 пережил блокаду. При ощутимом влиянии М.П.Мусоргского основу муз. яз. М. составляют еврейский мелос и интонации синагогальной музыки. Автор 3 опер (тексты на идише): «Небеса пылают» (1923,Петроград; снята после 3-го спектакля как «реакционная»), «Новый путь» (1933), «Флавий» (по ром. «Иудейская война» Л.Фейхтвангера, 1933–43, не окончена), бал. «Асмодей», симф. (1937), симф. поэм «Юдифь» и «Партизаны» (1944), симф. сюиты на еврейские темы, концерта для фп. с орк. (1946), хоралов (в т. ч. на тексты молитв, псалмов, стихов Х.-Н.Бялика, вок. сюиты (1916, на сл. И.-Л.Переца, поэмы для голоса с фп. «Суламифь» (1950), романсов (на сл. Г.Гейне, еврейских и рус. поэтов). ****Moshe Milner: In Chejderfor voice and pianoCover page of Milner\'ssong \"Der Schifer\",Kiev, Kulturliga 1922As a child Moshe (Michail) Milner (1886-1953) sang in the choirs of famous Chazzanim, including Nissan Belzer und Jakov Morogowski, later with Abram Dzimitrowski at the Brodsky Synagogue in Kiev. The financial support of the Brodsky family enabled him to attend the Kiev Conservatory. In 1907 he was admitted to the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he studied piano and composition until 1915.Under the influence of Susman Kiselgof, Milner became in 1911 affiliated with theSociety for Jewish Folk Music, which later published several of his works. In 1923 he conducted the première of his opera \"Die Himlen brenen\" - the first Yiddish opera in Russia; after two performances it was denounced as reactionary and forofferden.In the 1920s Milner wrote incidental music for different Jewish theaters: the Hebrew theater \"Habima\" (Moscow) as well as for the State Jewish Theaters (GOSET) in Moscow, Charkov and Biroofferzhan. In the 1930s he also was musical director of the Jewish Voice Ensemble (Evokans) in Leningrad. Among the composers of the New Jewish School Milner stands out through his vocal recitatives based on typical intonations of the Yiddish language. **** The New Jewish School can be compared to other national currents, forming the European musical landscape since the middle of the 19th century. While Russian, Czech, Spanish or Norwegian national music was able to unfold and establish itself in the cultural conscience, the development of the Jewish school was violently terminated by the Stalinist and national-socialist policy after only three decades.The history of the New Jewish School started in the first decade of the 20th century. In 1908 theSociety for Jewish folk musicwas founded in St. Petersburg - the first Jewish musical institution in Russia. Important composers, such asJoseph Achron,Michail Gnesin,Alexander Krejn,Moshe Milner,Solomon Rosowsky,Lazare Saminskyand others joined it. In contrast to Jewish composers from Western Europe these young artists did not lose their connection to the Jewish community. The more than five million Jews in Russia (at that time about half of the Jews in the world) lived in old traditions, which remained a nurturing soil and a source of inspiration for musicians.Initially, the activities of the Society concentrated on the collection, processing, publication and presentation of Jewish folklore. At the same time more and more original compositions were created, which were published in its own publishing company. Additionally, concerts, lectures and ethnologic expeditions were organized.By 1913, the Society already had more than one thousand members; subsidiaries were opened in seven cities. For young composers (about twenty five of them) the Society was a union of kindred spirits, where discussions could be held and a familiar atmosphere prevailed.As a result of the political and economic collapse in the years 1918 to 1921, the Petersburg Society and its subsidiaries in other cities had to discontinue their work. Most of the leading members from Petersburg emigrated during this time, while the members in Moscow had smaller losses. This is why the center o f Jewish music re-located from Petersburg to Moscow in the 1920s. In Moscow the Society could be revived.David Schor, the first president of the newly formedSociety for Jewish music, stressed in a lecture, that in contrast to the previous Society for Jewish folk music, performances, expenses and spreading of Jewish art music would be the center of attention.It was clear from the beginning that the activity of the Society would not attain the same dimensions as its predecessor. Its activities concentrated predominantly on concerts. These concerts played a crucial role for the new Jewish music, as they offered the composers a platform which they normally would not have had. This was especially an important incentive for young composers to devote themselves to Jewish music. In the years 1923 to 1929 hundreds of works (for the most part chamber music), some of which were exclusively composed for the concerts of the Society, were created in this way. The programs were worked out by a music commission, which included, among others, the composersMichail Gnesin, the brothersGrigoriandAlexander KreinandAlexander Weprik.One can judge the high standard of the Society by looking at the names of the performers. First-class Jewish and Russian artists, like the pianist Maria Judina or the members of the famous Beethoven quartet remained linked with the Society throughout the entire time of its existence.Starting in 1925 the Society for Jewish music was attacked by music officials for its repertoire. Serious signs of a crisis became evident at the end of 1927. The Society was increasingly steered by communists. They demanded a complete re-orientation, especially a repertoire that met the requirements of Jewish working people. The days of most Jewish cultural institutions were already numbered - the last event of the society is dated December 22nd, 1929. Jewish artists had to adapt to the reigning cultural doctrine of socialist realism and had to deny their Judaism.But at that time the New Jewish School was no longer confined to Russia. It also had a considerable influence on international Jewish musical life. Just as its activities in Russia had almost come to a standstill, this music spread throughout Europe, with Vienna as the most outstanding center. In 1928 aSociety for the Promotion of Jewish Musicwas founded in Vienna. Its most important composers wereIsrael Brandmann,Joachim StutschewskyandJuliusz Wolfsohn.Not only was the New Jewish School a victim of Stalinist antisemitic politics in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, but in other countries too its development was thwarted more and more by antisemitism. The final end came with NS-domination over West- and Central Europe, leading to the expulsion and murder of Jewish musicians. ****Society for Jewish Folk MusicAuthorYoel EpsteinViolins, Voice and JewsIn the spring of 1897, on the eve of the Russian Orthodox Easter, two Russian musicians met in an encounter that was to have impacts on classical and popular music to this day. Vladimir Stasov, music historian and promoter of the New Russian National School of “The Five” – Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui, Balakirev, Borodin and Moussorgsky – was introduced to the Russian Jewish composer and music criticJoel Engel. Stasov beratedEngel for abandoning his own heritage for the Slavic culture of Russian intellectuals. “Where is your national pride in the music of your own people!” shouted Stasov.According to Jacob Weinberg, a close friend of Engel’s, “The young Engel was overwhelmed, bewildered… [Stasov’s] words struck Engel’s imagination like lightning… this was the memorable night when Jewish art music was born.” From that moment, Engel dedicated his life to transcribing, arranging, and promoting the musical heritage of Russian Jewry. He inspired a group of likeminded musicians of Russian Jewish origin, who together formed the “St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music.” Members of the society included the violin virtuosoJoseph Achron, composer and pedagogueMikhael Gnessin, and a band of lesser known composers. The group developed a unique style that merged the melodic elements of Jewish folk and liturgical music – the music of the “klezmer” – with the rich harmonies of the late Russian romantic style. Central to this new style was the uniquely haunting timbre of voice and violin in duo. Their work was an influence on many later composers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, including Shostakovitch, Prokofiev, Milhaud, Bloch and others. They laid much of the foundation of modern art music written in Palestine and later Israel, as well as Israeli popular and folk music. Without their work, there would be no Klezmer revival as it is flourishing today.The Hebrew National StyleWhile each of the composers of the new Hebrew national school had his own style, there are a number of clear common characteristics. First and foremost, these composers preferred the chamber or lied format over larger symphonic forms. True, there are a few symphonic works, but the vast majority of the works are for voice and piano, or for small string chamber groups.Voice and string ensemblesOne of the outstanding forms of the group was the song for voice, piano and either violin or viola. The voice-violin combination, such a favorite during the Baroque period, was virtually abandoned by the classical and romantic composers. Aside from the two songs opus 91 by Brahms for viola, contralto and piano, the romantic composers wrote almost nothing for this ensemble; Saints Saens wrote a few songs with violin/piano accompaniment, and Donizetti wrote a couple of songs. Schubert wrote lieder with obbligato clarinet and obbligato horn, but nothing for violin or viola.It is somewhat surprising, then, that these composers chose to write extensively for this combination. No doubt the importance of the violin in Jewish folk music of the time played a deciding role in their choice. The violin was the instrument of choice, and was almost ubiquitous, in Jewish households. “How do you know how many men live in a house?” asked Yiddish author Y.L. Peretz. “Count the fiddles hanging on the wall – that’s how many men there are.” ****Jewish art music movementFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia(Redirected fromSociety for Jewish Folk Music)Jump to navigationJump to searchshowThis articlemay be expanded with text translated from thecorresponding articlein Hebrew.(June 2015)Click [show] for important translation instructions.TheJewish art music movementbegan at the end of the 19th century in Russia, with a group of Russian Jewish classical composers dedicated to preserving Jewish folk music and creating a new, characteristically Jewish genre of classical music. The music it produced used Western classical elements, featuring the rich chromatic harmonies of Russian late Romantic music, but with melodic, rhythmic and textual content taken from traditional Jewish folk or liturgical music. The group founded theSt. PetersburgSociety forJewish Folk Music, a movement that spread to Moscow, Poland, Austria, and later Palestine and the United States. Although the original society existed formally for only 10 years (from 1908 to 1918), its impact on the course of Jewish music was profound. The society, and the art music movement it fostered, inspired a new interest in the music ofEastern EuropeanJewrythroughout Europe and America. It laid the foundations for the Jewish music andKlezmerrevival in the United States, and was a key influence in the development ofIsraeli folk and classical music.With the outbreak of World War I and the rise of Communism in Russia, most of the composers active in the Jewish art music movement fled Eastern Europe, finding their ways to Palestine or America. There, they became leaders of the Jewish musical communities, composing for both synagogue and the concert hall.Contents1 Origins2 The St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music3 Jewish art music outside Russia4 Footnotes5 References6 External linksOrigins[edit]The interest in Jewish national music coincided with the nationalist trends in music throughout Eastern Europe. In Russia, composers led byRimsky-Korsakov, were composing new works based on Russian folk themes. In Hungary,Zoltán Kodályand laterBéla Bartókundertook a massive project of recording and cataloging folk melodies, and incorporating them into their compositions. Other composers such asAntonín DvořákandLeoš Janáčekwere increasingly seeking a uniquely national sound in their work. \"Europe was impelled by the Romantic tendency to establish in musical matters the national boundaries more and more sharply,\" wrote Alfred Einstein. \"The collecting and sifting of old traditional melodic treasures ... formed the basis for a creative art-music.\"[1]Parallel with this trend toward national music styles was an awakening of nationalist sentiment among theJews of Russiaand Eastern Europe. Long subjected to severe restrictions on their lives, outbursts of violent antisemitic pogroms, and forced concentration in a segregated region of Russia called thePale of Settlement,[2]Russian jewry developed an intense nationalist identity during the 1880s onward. This identity gave rise to a number of political movements - theZionist movement, which advocated emigration from Russia to Palestine, and theBund, which sought cultural equality and autonomy within Russia. There was a flowering of Yiddish literature, with authors likeSholem Aleichem,Mendele Mocher Sforimand others. AYiddish theatermovement started, and numerous Yiddish newspapers and periodicals were published.Violinist Joseph AchronIn spite of the restrictions on residency and quotas on Jewish students in universities, many Russian Jews enrolled as music students at theSt. PetersburgandMoscowConservatories. These included violinistJoseph Achron, composerMikhail Gnesin, and others. Many of the great violinists of the last century —Jascha Heifetz,Nathan Milstein,Efrem Zimbalist,Mischa Elman, to name a few — were Jewish students ofLeopold Auer, who taught at the conservatory.While many of these students came from orthodox Jewish backgrounds — Achron, for example, was son of a cantor — their studies of music at the conservatory were strictly of the western classical tradition. However, the rise of nationalism in Russian music also awakened an incipient interest in Jewish music. In 1895, Yiddish writerY.L. Peretzstarted collecting lyrics of Yiddish folksongs.[3]:28Abraham Goldfaden, founder of the Yiddish theater in Russia, incorporated many folksongs and folk style music in his productions.[3]In 1898, two Jewish historians,Saul Ginsburgand Pesach Marek, embarked on the first effort to create an anthology of Jewish folk music.[3]:26The main catalyzer of the movement for national Jewish music, however, wasJoel Engel. Engel, composer and music critic, was born outside the Pale of Jewish settlement, and was a completely assimilated Russian.[4]:33A meeting with the Russian nationalist criticVladimir Stasovinspired Engel to seek his Jewish roots. \"(Stasov\'s) words struck Engel\'s imagination like lightning, and the Jew awoke in him,\"[4]wrote Engel\'s friend and fellow composerJacob Weinberg, a Russian-Jewish composer and concert pianist (1879-1956) who joined the Moscow branch of the Society of Jewish Folk Music. Weinberg eventually migrated to Palestine where he wrote the first Hebrew opera, \"The Pioneers\" (Hechalutz) in 1924. Engel set out to study the folk music of the Jews of the Russianshtetls, spending the summer of 1897 traveling throughout the Pale, listening to and notatingYiddish songs. In 1900, he issued an album of ten Jewish songs, and presented a lecture concert of Jewish folk music.[3]:31The St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music[edit]A composition by H. Kopit, published by the Society. The cover sheet shows the logo that appeared on the Society\'s publications: a star of David enclosing a harp, flanked by a winged lion and a deer, recalling the Biblical verse \"Strong as a lion, quick as a deer.\"In 1908, Engel and a group of like-minded musicians from the Petersburg conservatory, (includingLazare Saminsky), founded the \"St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music.\" The objectives of the society were to develop Jewish music \"by collecting folksongs ... and supporting Jewish composers,\" and to publish compositions and research on Jewish music.[5]The society produced concerts, primarily of arrangements of folk melodies for various ensembles, and published arrangements and original compositions by its members. These included the composersSolomon Rosowsky,Alexander Krein,Mikhail Gnessin, and the violinistJoseph Achron.With the growing nationalist and Zionist sentiment among the Jewish population, these concerts were received enthusiastically. In a concert in the Ukrainian city of Vinitse, for example, \"the artists were met at the train and paraded through the Jewish part of the city with great ceremony and enthusiasm,\" recollected the local cantor.[3]:48Among the artists performing in these concerts were violinistsJascha HeifetzandEfrem Zimbalist, cellistJoseph Pressand the bassFeodor Chaliapin.In 1912, the society sponsored an expedition that included the Yiddish musician and educatorSussman Kisselgoff, to record Jewish folk music using the newly invented Edison phonograph. The group recorded more than 1000 wax cylinders. The collection is preserved in theVernadsky National Library of Ukraine, in Kiev.[6]This collection is one of the most important ethnographic resources of Jewish life in Ukraine from that period. Another important endeavour of the society was the publication of a \"Song Collection for Jewish Schools and Home.\" This songbook was a monumental six volumes, and includes, in addition to folksongs collected by Kisselgoff and others, original art songs and a section on cantillation of religious texts.Jewish art music outside Russia[edit]The success of the society spread throughout Russia, and into eastern and central Europe. In 1913, a branch was founded in Kharkov, and later in Moscow and Odessa. The advent of World War I and the Russian Revolution put an end to the formal existence of the society, but its members continued their activities and influence in Russia and abroad. Polish Jewish musicians such as Janot Rotkin, inspired by the society, embarked on their own projects of gathering, arranging, and composing Jewish music. In 1928, the Society for the Promotion of Jewish Music was founded in Vienna.[7]With the onset of the Russian revolution, most of the leading members of the St. Petersburg society left Russia. Joel Engel moved to Berlin in 1922, where he established the Juwal Publishing house. There he republished many of the society\'s works. Two years later he moved to Palestine, and started Jibneh, which continued the publishing work of Juwal. He died in Palestine in 1927. A street in Tel Aviv now bears his name. Lazare Saminsky emigrated to the U.S. in 1920, where he became a leading figure in the promotion of Jewish music. He was music director of theTemple Emanu-Elreform congregation in New York, a position he held until his death, in 1959.[8]In 1932,Miriam Zunser, together with Saminsky,Joseph Yasserand others, founded MAILAMM (known by its Hebrew acronym), an institute for the study and promotion of Jewish music in Palestine and the United States;[9][10][11]it was one of the predecessor organizations to the American Society for Jewish Music, which formed under that name in 1974.[9]Solomon Rosowsky moved to Palestine, and later to the United States, where he continued composing, teaching and researching Jewish music.Jacob Weinberg moved to Palestine in 1922 after being persecuted in Odessa by the Bolsheviks. In 1927 his opera \"The Pioneers\" won first prize in the Sesquicentennial composition contest. With the prize money, he was able to migrate to New York. His religious works were performed in New York City at Temple Emanuel, (where he became a \"house composer\"), as well as the Park Avenue Syngagogue and the 92nd St. Y. He joined the music faculty of Hunter College and the (now defunct) NY College of Music. He continued to compose, perform, and teach. His comic opera, \"The Pioneers\" (\"Hechalutz\") (1924) was performed in concerts at Carnegie Hall in February, 1941 and again in February, 1947, and in the 1930s at City Center (then called \"The Mecca Temple\", with its Moorish architecture). It was also performed in Berlin in the 1930s by the Kulturbund, featuring the great soprano Mascha Benya. Her aria \"Song of Solomon\" was more recently performed in 1998 by soprano Harolyn Blackwell at Lincoln Center\'s Avery Fisher Hall in a gala \"Salute to Israel\'s 50th Birthday\" concert conducted by Leon Botstein with the American Symphony Orchestra. A production of \"The Pioneers\" is planned for Brooklyn College in the fall, 2015 to celebrate the opening of their new performing arts center. A concert version of this opera was produced by his granddaughter, Ellen L. Weinberg, in NYC in 2012 and can be seen on YouTube. ****Society for Jewish Folk MusicContentsHideSuggested ReadingAuthorIn its brief existence (1908–ca. 1919) the Society for Jewish Folk Music (Rus., Obshchestvo Evreiskoi Narodnoi Muzyki; Yid., Gezelshaft far Yidisher Folks-Muzik) launched an influential movement among young Russian Jewish composers to create a modern national style of Jewish concert music. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, as part of the Russian Jewish intelligentsia’s growing interest in Jewish nationalism and Yiddish folk culture, musician and music criticYo’el Engeland historian-folklorists Peysekh Marek andSha’ul Ginsburgpromoted the study of Jewish folk music from thePale of Settlementthrough fieldwork, public lectures, and publications. These initial efforts, combined with the encouragement of Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, soon inspired a group of young Jewish musicians at theSaint PetersburgConservatory to organize the Society for Jewish Folk Music in 1908.The society’s early prominent membersincluded Lazare Saminsky, Efrayim Shkliar, Solomon Rosowsky,Aleksandr Krein, Mikhail Gnesin, and Joseph Achron. Its activity comprised four main areas: research, composition, performance, and publishing. Many individual members conducted ethnographic fieldwork, transcribing Yiddishfolk songs, klezmer melodies, Hasidicnigunim,and other forms of traditional Jewish music, which then served as the basis for the creation of modern concert-music pieces. The first compositions generally took the form of short, stylized arrangements for some combination of voice, piano, and strings or chorus. Over time, the works grew in originality and in formal and harmonic complexity, eventually including pieces for large chamber ensembles and orchestral arrangements. Stylistically, these works reflected a mixture of late Russian Romantic style with the emerging European modernist aesthetic.AUDIO\"Hebrew Melody.\" Music: Joseph Achron. Performed by Jascha Heifetz with orchestra directed by Josef Pasternack. Victrola 6160 mx. 21268-3, Camden, N.J., 1917. (YIVO)The society maintained a steady schedule of concerts, divided between small regular lecture-concerts for the Saint Petersburg membership devoted to various aspects of Jewish music and periodic large, public concerts typically held at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. In 1910, the society began its music-publishing efforts with an initial series of 15 compositions. Eventually the society and its various successor organizations would publish several hundred different pieces of music.The impact of the society extended beyond Saint Petersburg. Requests for membership, sheet music, and other assistance came from places as distant as Zurich, Edinburgh, Baltimore, and Tel Aviv. Within theRussian Empire, local branches were established in many cities, includingMoscow(1913),Kiev(1913), andOdessa(1916). Each branch distributed the society’s publications and sponsored lectures and concerts. In spite of its avowed Jewish nationalist orientation, the society did not pursue any one particular political affiliation, but collaborated comfortably with Zionist, Folkspartey, and liberal Jewish groups.In the years 1912 to 1914, members ofthe society also organized and participated in S. An-ski’sJewish Historical-Ethnographic Expeditionto the Pale of Settlement, resulting in an invaluable trove of musical transcriptions and early field recordings. Other projects included music classes and community choruses inbothSaint Petersburgand Moscow andtheLider-zamelbukh far der Yidisher shul un familie(Sbornik pesen dlia evreiskoi shkoly i sem’i[Anthology of Songs for theJewish School and Family]; 1st ed., 1912), a large, diverse collection of music that even included the works of non-Jewish composers such as Beethoven and Mozart.The onset of World War I disrupted but did not halt most of the society’s work. The main branch in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg), however, began to encounter various technical difficulties regarding music publishing and maintaining contact with other branches. At the same time, the Moscow chapter, under the active leadership of Engel, grew in scope and importance during the war years. Relations between Petrograd and Moscow deteriorated, owing to communication problems and to the Moscow chapter’s growing sense of independence. In addition, the chaos and destruction of the revolution in 1917–1918 led to a further breakdown in the authority and organizational structure of the organization. It was in this context that the Moscow branch in 1918 formally reorganized itself as the Obshchestvo Evreiskoi Muzyki (Society for Jewish Music), initiating music publishing under its own name. Concerts and meetings did continue to take place in both Moscow and Petrograd through at least 1919, the last year that either of the two groups functioned at full capacity.The Russian Revolution split the society in three different geographic directions. Activities in Petrograd continued in 1918 and 1919 with the support of the new Bolshevik state through the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment. Unsuccessful attempts were also made to relaunch publishing activities in partnership with the Kiev-basedKultur-lige. But by the early 1920s the political and cultural focus of Jewish life had shifted to Moscow. There, a new version of the Society for Jewish Music was formally organized in 1923. In drastically different political, social, and cultural conditions, but with government recognition and support, this society presented concerts, pursued fieldwork, and published music through 1929. In this way, much of the compositional legacy of the organization was continued, as composers such as Krein, Gnesin, Aleksandr Veprik, and Moyshe (Mikhail) Milner produced an impressive range of Jewish concert music, including opera, ballet, symphonies, and Yiddish theater.Various efforts were made to continue the publishing and performance legacy ofthe society in Central Europe. Soon this work shifted to Jewish Palestine, where both Yo’el Engel and Solomon Rosowsky immigrated in the 1920s. There the society’s cultural model of Jewish national music influenced many Zionist composers and critics. New York became a third main center of activity, drawing many other former members settled, notably Lazare Saminsky, Leo Zeitlin, and Joseph Achron. Sporadic attempts to restart some version of the society eventually resulted in the founding of the American-Palestine Music Association (Makhon Erets Yisra’eli le-Mada‘e ha-Musikah; Mailamm) in 1932, followed in 1939 by the establishment of the Jewish Music Forum, which continued much of the academic and artistic legacy of the group into the 1960s, eventually emerging as the American Society for Jewish Music. Intellectually and artistically, the society remained an influential model for both academic scholars of Jewish music and composers of Jewish concert music throughout the twentieth century. The end of the Soviet Union and the opening of Soviet archives has led to a noticeable revival of interest in the society’s history and music, as demonstrated by concerts, conferences, publications, and recordings in Russia, Europe, Israel, and the United States. ***SOCIETY FOR JEWISH FOLK MUSIC, society founded in St. Petersburg in November 1908 by a group of Jewish students at the conservatory there and their friends, among themSolomon *Rosowsky,Lazare *Saminsky, A. Zhitomirsky, and A. Niezwicski (Abileah). It was originally intended to be a \"Society for Jewish Music,\" but the commanding general of the district refused to license it under this title because he doubted whether true Jewish music existed, although he conceded that there must be Jewish folk music. The word folk was therefore inserted in the name and constitution. An important circle of Jewish musicians with similar interests had already formed in Moscow c. 1894 aroundJoel *Engel, and the first concert of the material they had collected and arranged was held there in 1900. This and similar groups now coalesced with the society in St. Petersburg.Joseph *Achron,Moses*Milner,Mikhail *Gnesin,Joseph *Yasser,Alexander *Veprik, andAlexander *Kreinsoon joined its ranks. In 1912 the Society already had 389 members with chapters in Moscow, Kiev, Kharkov, and Odessa. In 1918 it was disbanded by the Soviet government as \"not conforming to the spirit of the time,\" but the influence of its ideology and actions persisted both among the members who remained in Russia and among those who left to settle in Western Europe, the United States, andPalestine. The Society\'s constitution did not fully reflect its unwritten ideology, and its provisions were never carried out in full. These are quoted here because all subsequent organizations for the promotion of Jewish music followed the same basic pattern. The aim of the society was \"to promote the research and development of Jewish folk music – religious andsecular– by the collection of folk songs and their harmonization, and to aid Jewish composers.…\" For this purpose the Society was to issue publications of music and musical research; to organize meetings, concerts, operatic performances, and lectures; to form a choir and orchestra of its own; to found a library; to publish a periodical; and to organize competitions and award prizes for \"musical works of Jewish character.\" An ensemble of singers and instrumentalists was founded which undertook many concert tours. Expeditions went to the Vitebsk and Kherson regions, and the melodies they collected were given to various composers for harmonization. Dozens of these works were published. Kisselgoff, Zhitomirsky, and Lvow also published theLider Zamlbukhwith arrangements of folk and art material \"for school and home use.\" In 1915 the society was stirred up by the controversy between Saminsky and Engel, in which Saminsky questioned whether the indiscriminate gathering and propagation of any and every tune taken from the \"folk\" really represented Jewish music, and pressed for a more discerning search as well as for the recognition of the greater authenticity of the liturgical traditions. Saminsky\'s visits to the Jewish communities in the Caucasus and Turkey confronted him with the reality of a Jewish musical tradition outside theAshkenaziculture which he had already surmised was neither less and perhaps even more authentic than that of Eastern Europe. Another controversy arose between Engel and*ShalomAleichem– Engel denying and Shalom Aleichem advocating the recognition of the songs ofMark *Warshawskias true folk songs. Discussions of what constituted Jewish music were also frequent and there was an intense nationalistic spirit (although most of the society\'s leading members, with the exception of Engel, did not identify directly with the Zionist movement). Engel\'s foundation of the Juwal-Verlag in Berlin was the last (actually posthumous) direct result of the society\'s endeavors. Its ideals were carried to the United States, where they were propagated by Saminsky, Yasser, Rosowsky, and Achron, and to Palestine where this was done by Engel himself. After his death in 1927, they continued to exert a strong influence on musical developments in theyishuvthrough Menashe Ravina andJoachim *Stutschewsky. *****Joel (or Yoel) Engel(Russian:Юлий Дмитриевич (Йоэль) Энгель,Yuliy Dmitrievich (Yoel) Engel, 1868–1927) was a music critic, composer and one of the leading figures in the Jewish art music movement. Born in Russia, and later moving to Berlin and then to Palestine, Engel has been called \"the true founding father of the modern renaissance of Jewish music.\"As a composer, teacher, and organizer, Engel inspired a generation of Jewish classical musicians to rediscover their ethnic roots and create a new style of nationalist Jewish music, modelled after the national music movements of Russia, Slovakia, Hungary and elsewhere in Europe. This style—developed by composers Alexander Krein, Lazare Saminsky, Mikhail Gnesin, Solomon Rosowsky, and others—was an important influence on the music of many twentieth-century composers, as well as on the folk music of Israel. His work in preserving the musical tradition of the shtetl—the 19th-century Jewish village of eastern Europe—made possible the revival of klezmer music today. ***5406

JUDAICA Ketubah Unique Buenos Aires 1923 Argentina 50x30 cm Wedding Book $450.00

1923 Proclamation to Jewish workers, in Hebrew - Judaica Poland $59.00

13TH ZIONIST CONGRESS POSTCARD PC ILLUST HERMANN STRUCK JUDAICA 1923 ZUCKERBERG $75.00

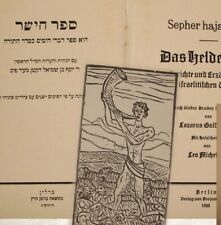

Jewish Judaica 1923 Germany Berlin Hebrew German Book Woodcut Art ספר הישר $39.00

1923 JEWISH PC IN YIDDISH NEW YORK TO PALESTINE PAID REPLY MISSING JUDAICA $35.00

1923 SEFER HAYASHAR BERLIN WOODCUTS ILLUSTRATIONS LEO MICHELSON JUDAICA BOOK $60.00

Shevet Mussar Lublin 1923 Yiddish 2 Volumes In One Antique Collectible Judaica $399.00

1923 Judaica SONG BOOK Yiddish RUSSIAN -ST. PETERSBURG SOCIETY JEWISH FOLK MUSIC $164.50

|